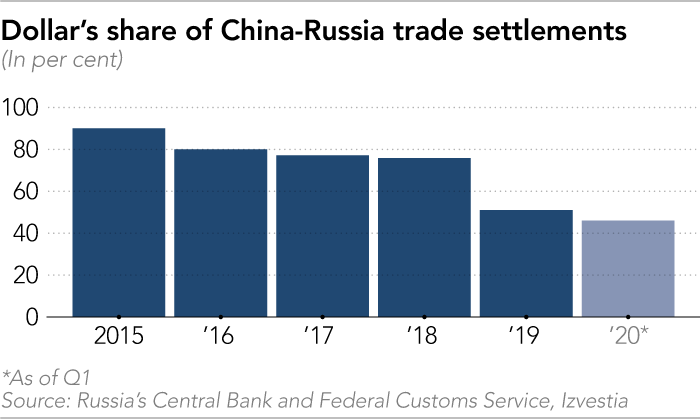

Russia and China are partnering to reduce their dependence on the dollar — a development some experts say could lead to a “financial alliance” between them. In the first quarter of 2020, the dollar’s share of trade between Russia and China fell below 50 per cent for the first time on record, according to recent data from Russia’s Central Bank and Federal Customs Service. The greenback was used for only 46 per cent of settlements between the two countries.

At the same time, the euro made up an all-time high of 30 per cent, while their national currencies accounted for 24 per cent, also a new high. Russia and China have drastically cut their use of the dollar in bilateral trade over the past several years. As recently as 2015, approximately 90 per cent of bilateral transactions were conducted in dollars. Following the outbreak of the US-China trade war and a concerted push by both Moscow and Beijing to move away from the dollar, however, the figure had dropped to 51 per cent by 2019.

Alexey Maslov, director of the Institute of Far Eastern Studies at the Russian Academy of Sciences, told the Nikkei Asian Review that the Russia-China “de-dollarisation” was approaching a “breakthrough moment” that could elevate their relationship to a de facto alliance. “The collaboration between Russia and China in the financial sphere tells us that they are finally finding the parameters for a new alliance with each other,” he said. “Many expected that this would be a military alliance or a trading alliance, but now the alliance is moving more in the banking and financial direction, and that is what can guarantee independence for both countries.”

De-dollarisation has been a priority for Russia and China since 2014, when they began expanding economic co-operation following Moscow’s estrangement from the west over its annexation of Crimea. Replacing the dollar in trade settlements became a necessity to sidestep US sanctions against Russia. “Any wire transaction that takes place in the world involving US dollars is at some point cleared through a US bank,” said Dmitry Dolgin, ING Bank’s chief economist for Russia. “That means that the US government can tell that bank to freeze certain transactions.”

The process gained further momentum after the Trump administration imposed tariffs on hundreds of billions of dollars worth of Chinese goods. Whereas previously Moscow had taken the initiative on de-dollarisation, Beijing came to view it as critical, too. “Only very recently did the Chinese state and major economic entities begin to feel that they might end up in a similar situation as our Russian counterparts: being the target of the sanctions and potentially even getting shut out of the Swift system,” said Zhang Xin, a research fellow at the Center for Russian Studies at Shanghai’s East China Normal University.

In 2014, Russia and China signed a three-year currency swap deal worth Rmb150bn ($24.5bn). The agreement enabled each country to gain access to the other’s currency without having to purchase it on the foreign exchange market. The deal was extended for three years in 2017.

Another milestone came during Chinese president Xi Jinping’s visit to Russia in June 2019. Moscow and Beijing struck a deal to replace the dollar with national currencies for international settlements between them. The arrangement also called for the two sides to develop alternative payment mechanisms to the US-dominated Swift network for conducting trade in roubles and renminbi.

Beyond trading in national currencies, Russia has been rapidly accumulating renminbi reserves at the expense of the dollar. In early 2019, Russia’s central bank revealed that it had slashed its dollar holdings by $101bn — over half of its existing dollar assets. One of the biggest beneficiaries of this move was the renminbi, which saw its share of Russia’s foreign exchange reserves jump from 5 per cent to 15 per cent after the central bank invested $44bn into the Chinese currency. As a result of the shift, Russia acquired a quarter of the world’s renminbi reserves. Earlier this year, the Kremlin granted permission to Russia’s sovereign wealth fund to begin investing in renminbi and Chinese state bonds.

Russia’s push to accumulate renminbi is not just about diversifying its foreign exchange reserves, Mr Maslov explained. Moscow also wants to encourage Beijing to become more assertive in challenging Washington’s global economic leadership. “Russia has a considerably more decisive position toward the United States [than China does],” Mr Maslov said. “Russia is used to fighting, it does not hold negotiations. One way for Russia to make China’s position more decisive, more willing to fight is to show that it supports Beijing in the financial sphere.”

Dethroning the dollar, however, will not be easy. Jeffery Frankel, an economist at Harvard University, told Nikkei that the dollar enjoyed three major advantages: the ability to maintain its value in the form of limited inflation and depreciation, the sheer size of the American domestic economy, and the United States having financial markets that are deep, liquid and open. So far, he argued, no rival currency has shown itself capable of outperforming the dollar on all three counts.

Yet Mr Frankel also warned that while the dollar’s position is secure for now, spiralling debts and an overly aggressive sanctions policy could erode its supremacy in the long run. “Sanctions are a very powerful instrument for the United States, but like any tool, you run the risk that others will start looking for alternatives if you overdo them,” he said. “I think it would be foolish to assume that it’s written in stone that the dollar will forever be unchallenged as the number one international currency.”

By Dimitri Simes for the Financial Times.