Under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, China underwent massive economic reforms in 1978. Since then, China has been the fastest-growing major economy with growth rates averaging 10% over 30 years.

China’s developing grip on the world is evident, according to the 2020 Global Financial Centres Index, having four of the world's top ten most competitive financial centres, more than any other country.

Additionally, China has three out of the ten world's largest stock exchanges, Shanghai, Hong Kong and Shenzhen by market capitalization and trade volume. China is an export-led economy, with a current account amounting to 1% of GDP, but this figure has fallen since 2016, where it sat at 1.8% of GDP as a result of the Trump Administrations aggressive tariffs against Chinese products.

Nevertheless, it looks like China intends on keeping its grip as the manufacturer of the world, or it would like to at least keep some form of influence on the global economy with its Belt and Road Initiative.

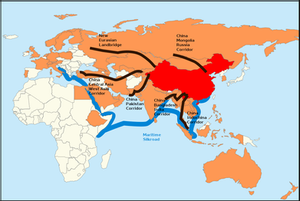

The Belt and Road Initiative was first unveiled by Xi Jinping in September and October 2013, the scheme involves China building a railway trade route from East Asia to Europe, as well as a Maritime Silk Road which stretches through several contiguous bodies of water: the South China Sea, the South Pacific Ocean, and the wider Indian Ocean area.

Additionally, Russia and China have agreed to build an Ice Silk Road which will be built along the Northern Sea Route in the Arctic. China expects to spend a total of $1tn towards the project including its vast network of railways, energy pipelines, highways, and streamlined border crossings.

The “One Road” part of the scheme will snake through less developed and developing, including India, which is on track to becoming an economic powerhouse in the future.

Therefore, once China loses its place as the manufacturing centre of the world, the belt and road scheme will still allow it to hold its influence in the world. This is because economies such as India, which may take China’s place in manufacturing power, will be reliant on the infrastructure provided by the Belt and Road Initiative.

Hence, if the scheme is a success, China will maintain its political and economic influence as its Belt and Road Initiative will become a key trade route that many developing nations, as well as developed ones, will use to export and import goods and services among the globe. It is likely that once it is built, it won’t be primarily Chinese products being transported, but products from many other countries due to the regional land monopoly China will have over trade-routes.

Furthermore, the additional land and marine-based trade routes which the scheme creates will reduce the risk of China becoming vulnerable to naval blocks. An expansion in the number of trade routes to which China has access too will allow them to still function well in the event of a naval block from the US, even if US forces do manage to cut China’s influence on the sea, the nation will still be able to export and import on land, although at a higher cost.

So, as well as increasing and maintaining China’s influence over the west, the Belt and Road Initiative makes it much harder for the US to do anything about China’s increasing influence. Apart from the increased tariffs which the Trump Administration has imposed on Chinese products, the US has done little to slow down the construction of the scheme or even oppose it.

The only significant mention of an increase in US influence within Asia was in 2014, where the then-Deputy Secretary of State William Burns committed the US to return Central and South Asia “to its historic role as a vital hub of global commerce, ideas, and culture.”

Consequently, the Obama Administration supported a $10 billion gas pipeline through Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. Billions of dollars were also spent on roads and energy projects in Afghanistan, this was then used to help create new diplomatic links with Central Asian countries.

With little opposition from the US, the main threat to the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative is BRI countries opposing Chinese influence. BRI funding is in the form of low-interest loans as opposed to aid grants, as a result, contractors have to pay increased costs which may lead to delays as well as political backlash.

Such a backlash occurred in Malaysia where the elected Prime-Minister in 2018, Mahathir bin Mohamad, campaigned against overpriced BRI initiatives. In-office, he cancelled $22 billion worth of BRI projects, although he later announced his “full support” for the initiative in 2019.

Hence, countries amounting large quantities of debt associated with the Belt and Road Initiative is a setback for China’s plans. Additionally, China has suffered a reduction in the amount of funding it can allocate towards the scheme, causing a slowdown in its deployment.

Overall, the lack of opposition from the US and the amount of power that China exerts over countries that try to oppose the scheme such as Malaysia will likely result in the scheme continuing but at a slower pace. Eventually, the completion of the scheme will increase China’s grip on the global economy; it’s inevitable that in the future, all roads will lead to China.

By Hubert Kucharski on March 23 2021 for the Back Seat Economist.