Kazakhstan is a linchpin for trade and transport links on the Eurasian continent – for China’s “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI) and beyond – due to its location, vast landmass and energy reserves. It is both the object and the subject of Chinese, Russian and Western geopolitical interests. The Kazakhstani case shows that the shape and success of the BRI largely depend on internal, not external, factors.

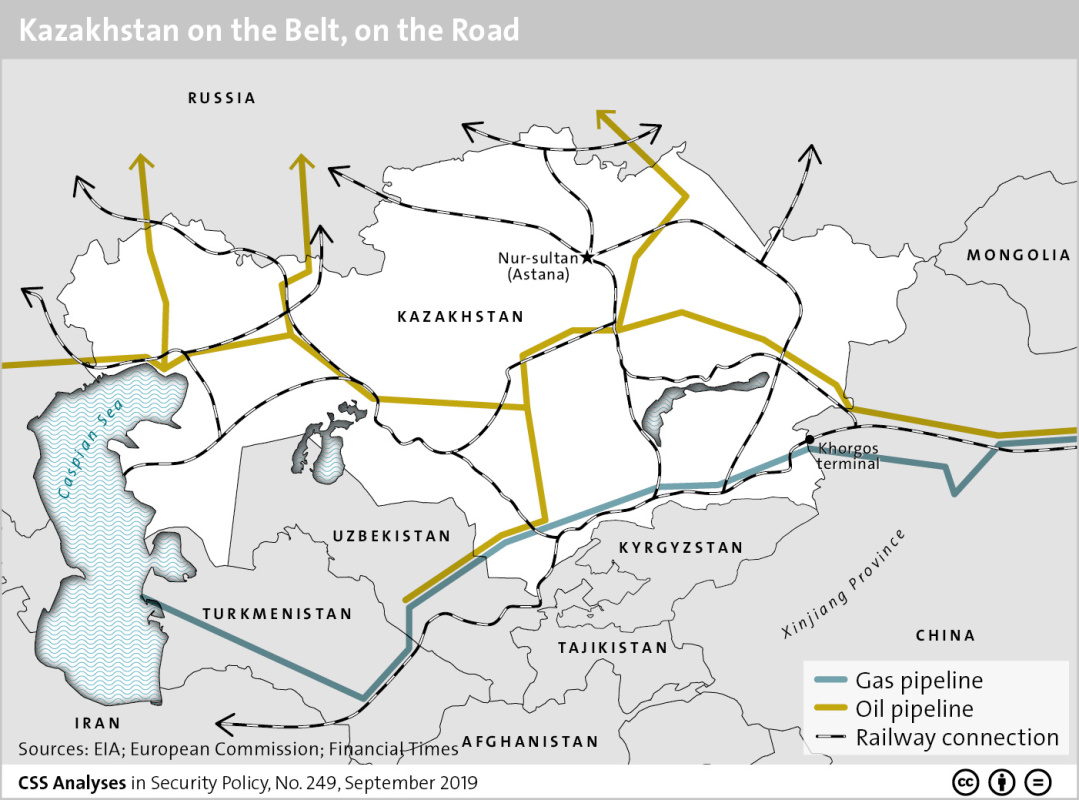

In September 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced an umbrella, a brand, for ambitious ongoing and future projects: “One Belt One Road”, now renamed the “Belt and Road Initiative”. This vague geo-economic and geo-strategic concept aims at fostering connectedness, economic development and diversifying trade and transport routes. The BRI entails Chinese-led investments in infrastructure and development projects in dozens of countries, worth an estimated 1 trillion dollars – a magnitude unprecedented in the 21st Century. Xi announced this project in Kazakhstan, which was no coincidence. While all Central Asian states hope to become BRI transit corridors and to benefit from investments, Kazakhstan, alongside Pakistan, was preconditioned to be a keystone of the land-based dimension of China’s plan, the Silk Road Economic Belt. Occupying a vast landmass in Eurasia and boasting large oil and mineral reserves, Kazakhstan holds an important geo-strategic position. China considers Kazakhstan crucial for transit, a source of energy and as a stable neighbour of its unstable Xinjiang province. It has invested billions in Kazakhstan’s energy and transport infrastructure, already prior to the BRI. At the same time, Kazakhstan is Russia’s closest ally in Asia. Moscow’s clout and societal, economic, political and military ties are strong. The West has little leverage to match China and Russia’s and is mostly interested in stability in Afghanistan’s neighbourhood and in Kazakhstan’s oil and uranium.

Kazakhstan officially pursues a ‘multi-vector’ foreign policy of good relations with all of these actors and tries to balance and compensate relations with one or the other. Geopolitical accounts often overlook this dimension of local agency and perceptions. This also includes the influence of cooperation and competition among the Central Asian states. The Kazakhstani government has eagerly embraced Chinese efforts to establish Kazakhstan as a regional transit hub because they were in line with its own national development strategies and assumed a high degree of ownership of the BRI on its territory. However, perceptions of China and its activities in Kazakhstan differ.

While the elite has been able to benefit materially, the population is very sceptical of China. The expert community points to China’s increasing influence and economic dependency. For countries beyond Central Asia, examining Kazakhstan’s experience may allow insights on the BRI, the challenges and opportunities a rising China offers, and their interaction with local politics and other powers’ geopolitical interests. The Kazakhstani case shows that the BRI’s manifestation and potential of success is as much a reflection of the political structure of the host country as of China.

Kazakhstan became independent after the demise of the Soviet Union. It is the ninth largest country in the world, with a population of only 18 million. First President Nursultan Nazarbayev established a system of ‘soft authoritarianism’. Elections have been a farce; political opposition and free media are severely restricted. Corruption is rampant and the elite has amassed large fortunes. Kazakhstan is currently in the course of a political leadership transition. Nazarbayev remains in powerful positions and his hand-picked successor, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, is set to maintain the current system, apart from a reshuffling of posts through which some win and some lose access to rents. Dissatisfaction among the population about the illegitimate accumulation of wealth and about inequality is widespread. Thousands of protestors voiced anger about their lack of political participation in spring 2019, but the political elite is unwilling to embrace fundamental reforms.

Brain drain to Russia as well as to the West has been an issue for years. Whereas Kazakhstan’s political system is authoritarian, the regime has pursued a fairly liberal economic policy and maintained elements of the welfare state, such that some of the wealth has trickled down to the population. Average income levels are on par with Russia’s and thus higher than in the region or in China. As Kazakhstan accounts for 60 percent of Central Asia’s GDP, it attracts up to a million migrant workers from its poorer neighbours.

Its impressive levels of economic growth have been fuelled by Kazakhstan’s vast wealth of hydrocarbon resources and minerals. It boasts the 11th largest oil reserves in the world. Additionally, Kazakhstan is the number one producer of uranium and has some of the world’s largest deposits of copper, phosphorite, zinc and gold. As resource wealth has filled the state’s coffers, dependency on the extractive sector has increased, despite the ensuing vulnerability from global markets and prices. The government acknowledges this overdependence and is eager to diversify its economy. It emphasised the need to boost agriculture and pursue infrastructure projects to foster trade and establish Kazakhstan as a trade and transit hub, already before the BRI was announced.

The need for enhanced connectedness for the world’s largest landlocked country is undebated and was also addressed by multilateral institutions like the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development or the Asian Development Bank. The latter has to date invested 5 billion dollars in Kazakhstan in road, railway and power generation projects, for example.

Kazakhstan under Nazarbayev has cultivated a good image abroad and pursued a balanced foreign policy of good relations with all major powers. It is a member of regional multilateral institutions like the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO), as well as the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO).

Kazakhstan’s relations with its northern neighbour are close, though not entirely by choice. It shares the longest border in the world with Russia, similar political systems, and economic and transportation links such as pipelines and railways. To this day, ethnic Russians are a sizable minority of around one quarter. The Russian language and media are widespread and a tool of considerable Russian soft power and influence. The legacy of the Soviet Union and the perception of cultural proximity, particularly among the urban population, are strong. While Kazakhstan’s defence forces have started purchasing equipment in China, Russia is the undisputed leading partner in the security and military sphere.

However, the Kazakhstani government has been wary of being subdued to Russian interests. It abstained from supporting Russian countersanctions against the West after 2014 and opposes the transformation of the EAEU into a political alliance. Relations with the West are largely limited to energy and security. European and US companies hold large shares in Kazakhstan’s hydrocarbon sector, for which their technology has proven crucial. Currently, one third of Kazakhstan’s exports go to the EU – virtually all of it raw materials like crude oil and minerals. Politically, there is no grand narrative or unified European approach to Central Asia or Kazakhstan more specifically. The US has mostly looked at Kazakhstan through a security lens as a neighbour of its two biggest rivals and of Afghanistan. It is guided by a vague New Silk Road strategy, announced in 2011, that largely lacks tangible results. The West has regularly criticised Kazakhstan for its restricted civic liberties, media freedom and unfair elections. Given its limited clout in the region, it has been unable to induce significant change.

Starting in the mid-1990s, Kazakhstan’s ties to China have intensified. The BRI has given them the latest boost. For China, implementing the BRI’s goals may have been imaginable without Kazakhstan’s participation, but only at substantially higher costs, risks and detours. China’s activities in Kazakhstan are mainly guided by three domestic motivations: energy security, diversifying trade routes, and domestic development and stability. They are underpinned by the fundamental geo-economic logic of the BRI: stability and security, which China tries to establish in its neighbourhood, can be achieved through economic development.

As the world’s largest energy importer, China is attempting to diversify its energy sources. The larger part of its oil supply is provided by potentially unstable countries in Africa and the Middle East and reaches China though the bottleneck of the Malacca Straits and waters largely dominated by the United States and its allies. Consequently, securing supply over land, from stable Central Asia, already became a strategic priority in the 2000s, prior to the BRI. Kazakhstan is crucial to this endeavour both as a supplier, particularly of oil and uranium, and as a transit country, for example for gas from Turkmenistan, China’s largest gas supplier. Connectivity and infrastructure links are a central element of the BRI. Enhanced road and railway infrastructure in Kazakhstan helps Chinese goods reach markets. Rail transport as opposed to shipping, albeit more expensive, cuts transport times from China to Western Europe in half. An outlet westward not only fosters exports overall, but also allows China to develop its largely neglected hinterland, including the province of Xinjiang bordering the Central Asian republics. The Uyghurs, a local Muslim minority, have been portrayed as destabilising and harbouring extremist and separatist sentiments. China is attempting to ‘pacify’ Xinjiang by pouring in investments, installing a comprehensive surveillance system and sending up to a million Muslims, among them many ethnic Kazakh, into ‘re-education camps.’ Good relations with China’s largest western neighbour, Kazakhstan, are thus critical to China’s domestic interests. Accordingly, and at an accelerated pace since the announcement of the BRI, China has invested vast funds in Kazakhstan. It had already purchased stakes in oil fields and built major pipelines in the 2000s. China granted a loan of 10 billion dollars in 2009 in exchange for more shares in the oil and gas sector.

A major element of Kazakhstan becoming a BRI transit hub between East and West has been the Khorgos container hub at the border, a Kazakhstani-Chinese joint venture, the world’s largest dry port and a BRI flagship project. Currently and mostly through Khorgos, Kazakhstan handles 70 percent of goods transited over land between China and the EU. A further element of the BRI is the outsourcing of China’s excess production capacity. In 2016, China and Kazakhstan agreed to move 51 facilities in sectors like smelting, engineering or chemicals worth more than 25 billion dollars to Kazakhstan. To date, only a handful have materialised. There is widespread concern that many of these projects may fail to fulfil environmental standards and to meet the demand of Kazakhstan’s market. Lastly, the BRI in Kazakhstan also has a societal element. China generously hands out scholarships. Currently, close to 18 000 Kazakhstanis are studying in China, and China runs five Confucius Institutes – educational institutions promoting Chinese culture and language – across Kazakhstan.

Kazakhstan as an early and stable partner of the BRI has chosen a distinct approach to it. In the road and rail sector in Kazakhstan, for example, China supports ongoing BRI infrastructure projects worth more than 5 billion dollars until 2022. This amount is matched by BRI projects run and financed entirely by Kazakhstan. In fact, the majority of BRI projects implemented in Kazakhstan were planned and financed by Kazakhstan itself, mostly through its sovereign wealth fund or in cooperation with multilateral development banks. Early on, Kazakhstan integrated its national development strategies such as ‘Kazakhstan 2050’ with the BRI and thus assumed ownership of BRI on its territory. Kazakhstan has been keen to diversify its economic partners and is attractive and wealthy enough to do so. Officially, foreign direct investments from and debts held by China have never amounted to more than 10 percent of total stock. Accounting for Chinese investments rerouted through other countries, this number is likely to be higher though. Still, this stands in distinction from other countries in the region like Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan or Turkmenistan, who owe around half of their rising debt to China. In Kazakhstan, Chinese funds were welcome as a substantial addition to its own investments and it offered members of the elite further ways to benefit. Corruption, side payments and favouring companies with good political ties – in China or Kazakhstan – are part of the process. Kazakhstan’s political elite has thus remained mute about China’s policy in Xinjiang, for example, and embraced the BRI.

But among the population, the perceptions of China and of Chinese involvement are different. While Russia is perceived as culturally close, there is widespread scepticism towards China based on historical animosities, stereotypes, increasing dependence on a more populous neighbour, and repression in China’s Xinjiang province. There is an evident lack of mutual understanding and of knowledge about the other’s cultural space and the details of the BRI. Controversially, Chinese companies in Kazakhstan often bring their own employees and pay them higher salaries than locals receive, generating grievances. Occasionally, protests have flared up involving anti-Chinese sentiment, for example in 2016 against a change in the land code that would have allowed foreigners to lease land for up to 25 years. Local and international experts acknowledge the need for a modernisation of Kazakhstan’s infrastructure and some benefit of close relations with China to balance Western and Russian influence. At the same time, they point to a lack of transparency in BRI projects and investments, unresolved issues of cross-border water management, China’s increasing political clout and the potential for territorial disputes to re-emerge.

However, observers still emphasise the stable and largely positive relationship between Kazakhstan and China. In BRI countries such as Malaysia or Sri Lanka, major projects were halted due to backlash, debt repayment to China has become problematic or populations have voiced fundamental resentment about the BRI and Chinese interference. Kazakhstan thus seems to largely represents a success story of the BRI. Assessing the BRI It appears that most large-scale projects like the construction of railways, roads and pipelines in Kazakhstan are already implemented. While the BRI remains an ongoing project, BRI spending in Kazakhstan has decreased in recent years, in line with a general decline in spending levels under the BRI. However, as both Kazakhstan and China provide little insight into the terms of BRI projects, evaluating the economic benefits thus far is difficult. Large-scale projects in Kazakhstan are widely understood to involve malpractice due to a lack of rule of law and accountability. BRI projects can be assumed to be no exception.

An infrastructure project in Kazakhstan’s capital is daily commuters’ visible reminder of such malpractice: pillars for a light railway, for which Kazakhstan borrowed 1.5 billion dollars from the Chinese Bank of International Development, currently stand across the capital like a skeleton (see photo). The project was halted after funds started disappearing and the Chinese donor pulled out. The BRI flagship project at the Kazakhstani-Chinese border, the Khorgos terminal, saw the head of the free-trade zone arrested for accepting bribes.

Furthermore, the Khorgos terminal is still running way below capacity, which raises questions about its profitability. Generally, the mere transit of goods produced elsewhere will not provide enough revenue and jobs. Physical infrastructure alone, without the accompanying regulatory procedures and standards, can also foster trade only to a certain extent. The structures BRI projects are embedded in, the local regulatory environment and development efforts, will determine whether Kazakhstan can increase its share in value chains and attract further investments to strengthen sectors like agriculture or manufacturing. Moreover, regional and geopolitical dynamics have an influence on whether BRI projects reach their objectives. All Central Asian states compete in the hope of becoming transit corridors and of benefiting from the BRI. If they manage to cooperate to some extent – for which the current environment is more favourable after decades of mistrust – their prospects of regional benefits could improve.

Regarding geopolitics, the Kazakhstani case further shows the limits of Chinese soft power. Despite the vast sums provided to the ostensible benefit of both countries as well as investments in student exchange and in fostering a favourable image of China, Sinophobia among the population persists. Russia, despite losing some leverage in Kazakhstan, is still viewed favourably. The Kazakhstani government is likely to continue to balance external powers’ influence to ensure the stability of the country and the elite. Since they are united in their opposition to the US and its allies, whose interests in Kazakhstan loom in the second row, Russia and China will not allow for competition between them to openly manifest. As such, there is no geopolitical game currently at play around Kazakhstan, given that none of the actors is fully willing to play.

The success and cost-effectiveness of BRI projects, and whether they will be of benefit to the Kazakhstani people or only create a debt burden for future generations, will thus only play out in the long run. As a BRI front-runner, Kazakhstan provides some early insights into the ways in which the BRI interacts with geopolitics and local politics though. The Kazakhstani case illustrates that the success of the BRI has more to do with the country and its domestic political structures than China per se. Kazakhstan, a wealthy state with some institutional capacity to negotiate, design and assess projects, has been able to assume ownership of the BRI to some extent. In smaller states in Central Asia, China’s leverage is overwhelming. Whenever possible, Kazakhstan diversified donors, including multilateral development banks. However, the lack of transparency surrounding BRI projects in Kazakhstan increased distrust both of Chinese intentions and of local elites’ interests. Calling all projects ‘perfect’, as the Kazakhstani government tends to do, without providing respective data or without even assessing them, will hamper the effective adaptation of projects according to needs. Other countries with institutional and financial capacities like Kazakhstan may follow its diversification of funds, though they would be advised to avoid the BRI being designed as opaque and serving elite interests.

By Benno Zogg for CSS (Switzerland), original published in September 2019,