The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has helped to deepen China’s relationships with developing countries around the world and has served Beijing’s ambitions in regional economic development, international trade and China’s industrial development. But since the BRI’s launch, Beijing’s ambitions in international trade and industrial policy have evolved, and the BRI – designed explicitly as a flexible endeavour – has been adapted to accommodate Beijing’s changing preferences. Beijing’s changes to the scope of the BRI should not be taken to imply that the BRI has ever been tightly directed; on the contrary, the lack of a discrete institutional identity has been one of the defining characteristics of the initiative and is one of the challenges in analysing the BRI. But, by stepping back, it is possible to observe an evolving pattern of ambitions which Beijing has promoted through the BRI. At its outset, the BRI was partly designed to address the problem of economic development in Western China.

Far from the affluent ports of China’s east coast on the East and South China seas, Western China was (and, to a lesser extent, remains) poorly connected to international trade routes. Moreover, at the time of the BRI’s launch, Beijing was confronting a low-level insurgency in Xinjiang in Western China by the Turkistan Islamic Party terrorist group and saw Xinjiang’s large ethnic minority Uighur population as a threat to the region’s stability. Before Xinjiang became known for its large-scale detention of Uighurs in so-called re-education camps, China aimed to build stability in the region by boosting economic growth. To strengthen Western China’s economy, the BRI set out to improve trade and transport connectivity between the region and neighbouring countries to the west and south, and to export markets further afield, by investing in six overland trade routes and a maritime trade route, invoking the ancient Silk Road. These routes through Central Asia, South Asia and Southeast Asia would, moreover, mitigate China’s dependence on shipping through the Strait of Malacca, a maritime choke point between the Malay Peninsula and the Indonesian island of Sumatra, dominated by the United States. Beijing saw its dependence on the strait as a threat to its energy and economic security, because of the potential for the US Navy to block access in the event of a confrontation. In 2018, President Xi Jinping announced the objective of adding another maritime route – through the Arctic. The BRI quickly expanded to include countries with no direct connection to these corridors – in Africa, Europe, Latin America and Oceania. This expansion served Beijing’s wider industrial policy and addressed China’s overcapacity problem.

For projects that served Beijing’s industrial objectives, proximity to the six overland corridors was not relevant to their inclusion in the BRI. Other industrial objectives were gradually added to the mix. The Chinese government’s ‘13th Five-year Plan’, its programme of government for 2016–20, set out new industrial ambitions. As the overseas incarnation of its industrial policy, the BRI soon reflected these new goals. China’s attention turned first to the digital economy, with Beijing adopting the Digital Silk Road (DSR) strand of the initiative in 2015. Subsequently, Beijing trained its sights on other high-tech and knowledge industries, including green technology and health (including e-health and pharmaceuticals). This widening industrial scope has led the BRI to expand and adapt to accommodate the different market dynamics and commercial actors involved in each sector, and Chinese loans and investments in BRI countries have flowed to these different sectors over time.

Nevertheless, Beijing has not attached equal importance to all BRI projects. On the one hand, there is, unofficially, a ‘strategic tier’ of projects that are central to Beijing’s core interests and for which the impetus has come from Beijing. On the other hand, there is a ‘soft tier’ of projects that have been driven either by the commercial interests of Chinese firms and the local interests of players in recipient countries, in which case the impetus for the projects has come from outside the Chinese government, or by China’s soft-power concerns, with encouragement from Beijing. At least initially, the strategic-tier projects were concentrated along the BRI’s economic corridors and supported China’s trade connectivity and regional economic imperatives. However, as the BRI has evolved beyond physical-infrastructure projects, the importance of the corridors and the distinction between corridor and non-corridor countries has faded. It has become much more important for Beijing to ensure that foreign governments and overseas markets remain open to China’s leading companies in higher-value sectors of the economy – whether in digital technologies and services, green tech or other advanced industries identified as priorities by Beijing. Despite these evolving ambitions for the BRI, a key element of Beijing’s overall approach to the initiative has remained constant. Throughout, the BRI strategy has consisted of mobilising Chinese companies and public and private capital in the service of China’s geo-economic interests overseas, thus increasing Beijing’s footprint and influence around the world. By transposing China’s state capitalism to the international arena in this way, the BRI represents a form of mercantilism that no other state can currently replicate.

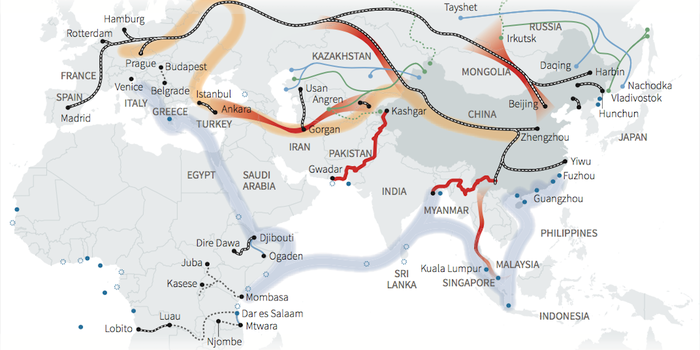

When Xi announced plans for the BRI in 2013, the foremost stated ambition was to improve ‘trade connectivity’ between China and certain regions of the world. But what exactly Beijing meant by trade connectivity has never been entirely clear. China has engaged in several tangible trade-related endeavours, including improving transport infrastructure in many partner countries and conducting a flurry of trade diplomacy, but the overarching ambition has remained broad and fuzzy. Central to Beijing’s ambitions for trade connectivity in the early years of the BRI were eight notional trade routes: six land-based economic corridors that comprised the ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ and two maritime trade routes that comprised the ‘21st Century Maritime Silk Road’. Plans for these trade routes were set out in 2015 by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the Chinese government department responsible for planning the BRI, in the ‘Vision and Actions’ plan. Xi reiterated plans for these corridors at the 2017 Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation (BRF),4 and in 2018 he announced ambitions for an additional maritime trade route through the Arctic. China–Mongolia–Russia Economic Corridor (CMR-EC) The China–Mongolia–Russia Economic Corridor is the northernmost land corridor. Before the BRI, the Trans-Siberian and Trans-Mongolian railways linked the three countries involved, but capacity on the Trans-Mongolian railway was limited and transit to China slow. The CMR-EC raised the possibility of better connectivity between China and the mining industries of both Mongolia and Russia. The route is also the shortest direct passage between northeast China and Europe (see ‘North and Central Asia’ chapter). New Eurasian Land Bridge (NELB) The New Eurasian Land Bridge is a route between China and Europe that passes through Kazakhstan and Russia. It connects with regional trade networks in Central Asia, which are particularly important to the regional economy of Western China, especially Xinjiang. The railway along this route provides the shortest distance between southern and western China, at one end, and Europe, at the other.

Plans for the China–Central Asia–West Asia Economic Corridor envisaged connective infrastructure (roads and railways) linking China with Europe and the Middle East along several routes through Central Asia, Iran and Turkey, and ultimately connecting to Europe’s railway network. Poor existing infrastructure and multiple changes of gauge have led to high development costs for this corridor and a slow route for goods to travel along the China–Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor was built on pre-existing plans for railways in Southeast Asia to link Kunming in China’s Yunnan province with Malaysia and Singapore along three routes: the western route via Myanmar and Thailand, the central route via Laos and Thailand, and the eastern route via Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand. The corridor would increase China’s connectivity to the growing economies of Southeast Asia and to the port of Singapore.

The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor was conceived shortly before the launch of the BRI but was quickly subsumed under it. The corridor stretches inland from the Chinese-run Gwadar Port on Pakistan’s Indian Ocean coast, ultimately reaching Western China. Highways and railways have been improved along the route, including the Karakoram Highway that connects the two countries through the challenging terrain of the Karakoram mountains; however, the idea of a railway and pipeline through the same mountain range has been shelved due to its economic unfeasibility (see ‘South Asia’ chapter). Bangladesh–China–India– Myanmar (BCIM) Economic Corridor Quadrilateral plans for a corridor linking Bangladesh, China, India and Myanmar predated the BRI, and Beijing included it among the BRI’s proposed corridors. However, India declined to participate in the BRI and rejected the inclusion of the BCIM Economic Corridor in the initiative, ensuring that subsequent discussions about such a corridor have taken place elsewhere. Those discussions have thus far yielded no progress

The Maritime Silk Road in the Indian Ocean and Mediterranean Sea Beijing’s primary plan for the Maritime Silk Road (MSR) has been to enhance China’s linkages by sea with Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, East Africa and, ultimately, Europe. This route was already a major artery for international trade, but the MSR would give China a bigger stake in the development of port infrastructure and in connected industries along the routes. It would also link up with several of the BRI’s overland corridors, particularly CPEC and CIP-EC. Maritime Silk Road in the Pacific Ocean Beijing also aims to improve the connection between China and the South Pacific, describing this route as the second strand of the MSR. Although China signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) on BRI cooperation with the Victoria state government in Australia – which was later scrapped by the Australian federal government – China’s efforts in the region have otherwise centred on the Pacific Island states

In 2018, Xi announced an additional strand of the BRI, the Polar Silk Road, which coincides with the Russian government’s plans for the Northern Sea Route. This maritime trade route passes through the Arctic Ocean along the north coast of Russia (known as the Northeast Passage), providing access to the natural-gas industry in Russia’s High North, and opening up an alternative shipping route to northern Europe that is 24% shorter than the route to Rotterdam via the Suez Canal. China has invested in a fleet of icebreakers to ply the route.

Chinese investments in and financing for transport infrastructure have been the central plank of the BRI’s efforts at trade connectivity. Since the announcement of the BRI, Chinese firms have invested over US$24 billion in greenfield transport-infrastructure projects, and Chinese policy banks committed US$71bn in loans for transport projects overseas between 2013 and 2017. However, only three of the trade routes listed above have actually received significant Chinese investment in transport infrastructure: the CIP-EC, the NELB and the MSR in the Indian Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. In the case of the CIPEC, China has provided the majority of the financing for the western and central routes, and Chinese contractors are leading the ongoing construction work on these routes, but as of early 2022, there is still no plan in place for the eastern route. The keystone project for the NELB has been the development of Khorgos Gateway Dry Port on the border between China and Kazakhstan, where customs processing and the changing of railway gauge takes place. (A railway already existed along the planned trade route.) Kazakhstan, rather than China, has taken the lead on developing the dry port, initially with DP World, an Emirati port operator. However, Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have subsequently taken a 49% share in the dry port and have worked closely with their counterparts in Kazakhstan to improve customs processes.

Along the MSR, several Chinese port projects – the improvement and expansion of existing ports and the development of new ones – were already in the works before the BRI came about, including, in Sri Lanka, at the ports of Colombo and Hambantota; in Pakistan, at Gwadar Port; in Djibouti, at Damerjog Port; and in Greece, at the Port of Piraeus. However, since then, Chinese involvement in ports has expanded to many more countries around the Indian Ocean, including Myanmar (with the development of a deep-water port and special economic zone at Kyaukpyu), Oman (with an industrial park at Duqm Port), Kenya (with the development of a new port at Lamu) and Mozambique (with the expansion of Beira Fishing Port). Long-running discussions continue with the government of Tanzania over a project to expand the port at Dar-es-Salaam. China has supported the creation of several other transport corridors which connect with the MSR, including the Ethiopia– Djibouti Standard-Gauge Railway (SGR) and Kenyan SGR in Sub-Saharan Africa, and the China–Europe Land–Sea Express Route from the Port of Piraeus in Greece to Budapest, Hungary. However, these bold, costly initiatives are less strategically important to Beijing than the BRI’s flagship economic corridors and the MSR itself. They have been driven more by the interests of partner governments, local actors and Chinese companies than by the interests of the Chinese government. (The limits of Beijing’s interests became obvious in the case of Kenya’s SGR, where only the first phase was built and Beijing refused to fund the latter phases of the project or build a connecting line in Uganda. The strategic gains from the project for China were evidently insufficient to balance the fiduciary risks of financing it.)

Besides financing and implementing transport-infrastructure projects around the world, China’s ‘trade connectivity’ efforts have also involved various trade diplomatic activities. The BRFs in Beijing, held so far in 2017 and 2019, have been the centrepiece of this trade diplomacy, bringing together representatives from the many states engaged in the BRI. At these jamborees, China has signed numerous trade and economic-cooperation agreements, several preferential trade agreements (PTAs) and many MOUs agreeing to negotiations on PTAs. Between 2014 and 2020, 33% of the BRI participant countries located along the BRI corridors signed PTAs with China. (By comparison, 9% of BRI participant countries located away from the corridors and 6% of countries not affiliated with the BRI signed PTAs with China.)

Initially, the BRI’s emphasis was on East–West connectivity between Asia and Europe. Xi’s speech at Nazarbayev University in Kazakhstan in September 2013 referred to his ambitions of ‘connecting the Pacific and the Baltic Sea’, creating a ‘belt’ of industry and transport linking the Eurasian continent. And in a speech before the Indonesian parliament the following month, Xi spoke of China’s ambition for a ‘21st Century Maritime Silk Road’, linking China and Southeast Asia with the Middle East and Europe by sea. At the time, European governments were enthusiastic about their growing trade with China. Moreover, the Eurasian orientation of the initiative avoided confrontation with the United States. However, in the intervening years, the focus of China’s BRI activity has shifted away from trade with Europe. There are several reasons for this evolution. Firstly, through the 2010s, growth was slow in Europe, the market on which much of the BRI’s ambition originally focused. Secondly, trade relations between China and Europe began to sour from around 2015, when European governments began imposing trade restrictions in retaliation for Chinese dumping of subsidised industrial goods, especially steel. Thirdly, Chinese trade with the West became vulnerable to greater political risk than in the early years of the BRI, as relations between Beijing and Western governments became fraught over a host of issues. Instead, China increasingly looks southward, especially to fast-growing markets in Southeast Asia, for continued growth in trade. Moreover, transport connectivity has become slightly less important for China as it has sought to move up the value chain: its export focus has moved away from exporting large weights and volume of low-value-added goods and towards exporting high-valueadded goods, such as digital infrastructure and services and renewable-energy technologies. Some of the economic corridors, especially to countries less likely to import Chinese high-tech goods, have lost some of their strategic value for Beijing.

There is a good economic rationale for China’s emphasis on trade connectivity. Several studies showed that if the BRI reduced the cost of transporting goods between China and partner countries, it would boost bilateral-trade volumes, particularly for countries along the BRI’s economic corridors (although China would be the main winner, with a larger increase in exports compared with its partners). Moreover, if economic cooperation between China and its trade partners led to improvements in customs processes, the boost to trade would be greater still.

However, the reality of China’s transport-infrastructure projects is that their impact on trade is, as yet, marginal rather than transformative. For example, trade between China and Europe has, for the most part, continued along the same maritime routes as plied before the BRI. Due to shipping backlogs during the coronavirus pandemic, some freight was diverted to road and rail across Eurasia but, in the grand scheme of China–Europe trade, the amount was small. Instead, better connections between China and its neighbours have improved China’s trade with Russia and Central Asia. This is still an important achievement, but it pales in comparison with the stated ambitions of the BRI. Likewise, there was never much prospect of a thriving trade route between Western China and Pakistan, despite the countries’ high hopes: it is simply uneconomical to transport goods via winding highways or railways through the Karakoram mountains for anything other than local trade. Despite the limited impact of the BRI on trade, China’s financing for transport infrastructure projects around the world has ensured the rapid growth of Chinese firms in the engineering and construction sectors. Between 2014 and 2020, Chinese companies received more than US$155bn in construction contracts in the transport and logistics sectors. China Communications Construction Company (CCCC), China Railway Construction Corporation (CRCC), China Railway Engineering Corporation, China State Construction Engineering Corporation, and Power Construction Corporation of China (PowerChina) – all SOEs – have become the five largest construction companies globally.

Another important goal for the BRI, especially in its early years, was to help alleviate China’s industrial overcapacity. Since before the 2007–09 global financial crisis, Chinese production capacity for steel, cement, aluminium, glass and ships had grown in excess of demand, leading, in some cases, to overproduction and, in other cases, underutilisation of existing capacity. Following the financial crisis, as the global economy entered a recession, global demand for these goods dropped further, and the overcapacity problem worsened. Chinese companies in these industries, many of them state-owned, had previously racked up debts to expand production domestically and were subsequently unable to achieve the operating profits they had anticipated.

The Chinese government hoped the BRI would help solve the overcapacity problem. Firstly, Chinese industry was encouraged to look overseas to invest in production facilities there, helping them to sustain growth and maintain profits. Secondly, Chinese-financed construction and power projects overseas would create demand for goods overproduced in China. An official from the Chinese Ministry of Industry and Information Technology spelled out the ambition: ‘For us there is overcapacity, but for the countries along the “One Road One Belt” route, or for other BRIC [Brazil–Russia–India– China] nations, they don’t have enough and if we shift it out, it will be a win–win situation.’ Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs He Yafei mirrored this view, highlighting the opportunity to use China’s overseas development strategy, namely the BRI, to ‘move out’ Chinese overcapacity. Moving metals overseas China’s steel and aluminium industries acted on Beijing’s cue and rapidly increased their investments overseas, particularly in BRI countries. However, trade, lending and investment data suggest that Chinese financed construction projects played little if any role in stimulating demand for Chinese materials. Chinese steel exports did grow quickly (in volume), especially to BRI countries, but this was due to China dumping subsidised steel overseas, not due to BRI lending or investment. (Steel exports to non-BRI countries in the West grew much less in volume due to counter-dumping measures.) Amid plummeting global steel prices, China pledged in 2016 to rein in its steel production and its exports dropped off thereafter – to BRI countries as well as to the West. This commitment did not extend to production by Chinese firms outside China, however, and their investment in steel production overseas continued to grow. In 2014–21, Chinese iron and steelmakers invested US$17.5bn in BRI countries, compared to US$4.7bn in the previous eight years. By contrast, Chinese cement and glass producers invested much less overseas, despite the fact that neither product could be easily exported (like steel or aluminium) due to the expense or difficulty of transporting them. Likewise, whether the BRI did anything to alleviate China’s overcapacity in shipbuilding – or whether Beijing ever intended it to do so – is less clear. Chinese investment in ports around the world is unlikely to have had an impact on the demand for ships built by China’s many shipyards.

Energy security has been a concern for Beijing since China became a net importer of oil in 1993. In 2007, it became a net importer of liquefied natural gas (LNG) and, in 2009, a net importer of coal. China’s new dependence on hydrocarbon imports raised questions about the security of supply – about where China imported these resources from and how the resources were shipped to China. Initially, China’s response was to reduce its dependence on imports from Southeast Asia (especially Indonesia, which provided 30% of China’s crude-oil imports in 1995) by increasing supply from the Middle East. But Beijing saw potential economic and political benefits from diversifying further, deepening ties to a wider array of countries around the world. Beijing directed China’s energy-sector SOEs to invest in energy production in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. Concurrently, China began to extend loans to oil-exporting states in Africa and Latin America, which would, in turn, sign purchasing agreements for oil with Chinese importers. By 2013, at least five African states (Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Ghana, Republic of Congo and Sudan) and three Latin American states (Brazil, Ecuador and Venezuela) had received these oil-backed loans. However, Beijing was also increasingly concerned about China’s reliance on the Strait of Malacca – the shipping lane through which it shipped much of its energy imports. If the US decided to deny China-bound oil tankers access to the strait, Beijing would face a serious threat to its energy supply. The first rumblings about this problem came in the 1990s and, by 2003, then-president Hu Jintao spoke about it publicly as the ‘Malacca Dilemma’.

As a result, even before the BRI, Beijing sought to increase energy imports via different routes. The first efforts came in 1997 when construction began on a Kazakhstan– China oil pipeline, jointly owned by China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), one of China’s ‘big three’ oil and gas majors, and KazMunayGas, Kazakhstan’s state-owned oil and gas corporation. In 2007, the same two companies began work on the Central Asia– China Gas Pipeline, a series of gas pipelines between Xinjiang and Turkmenistan, via Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. By 2010, two lines were operational.

In the years directly before the announcement of the BRI, China developed further plans for the diversification of its oil and gas imports. In 2009, CNPC’s parent company, PetroChina, began construction on two pipelines between Myanmar and China, one for crude oil and one for natural gas. And in 2012, CNPC began work on a third Central Asia–China gas pipeline. By the time these pipelines were completed, they had become flagship projects for the BRI, not least because they were located along some of the main BRI economic corridors: the China–Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor, the China– Central Asia–West Asia Economic Corridor and the New Eurasian Land Bridge. Additional projects followed. In 2014, CNPC concluded a gas-purchasing agreement with Gazprom, Russia’s leading gas company, enabling the construction of the Power of Siberia Pipeline to deliver gas to northeast China. Work also began on Line D of the Central Asia–China Gas Pipeline, although construction has been beset with delays. In 2022, China and Russia began work on a gas pipeline between Heilongjiang and Sakhalin. And the two countries, with Mongolia, pressed forward with plans for Power of Siberia 2, a pipeline from the Arctic via Mongolia. Discussions also continue on additional pipelines from Myanmar (for further details on these pipeline projects, see ‘North and Central Asia’ and ‘Southeast Asia’ chapters). Since the launch of the BRI, besides pipelines, Chinese companies have invested in new oil and gas fields, and refineries too. CNPC and China’s Silk Road Fund invested in Yamal LNG alongside Russia’s Novatek and France’s Total in a joint venture to develop a natural-gas field and port in the Russian Arctic, on the Northern Sea Route. The privately owned Chinese company Sherwood Energy invested US$11bn in a gas refinery in Russia’s Far East. And in 2020, Zhejiang Hengyi Group, a privately owned Chinese chemical company, announced the second-largest Chinese foreign investment globally, taking a 70% share in a US$13.7bn joint venture with the government of Brunei to develop an oil refinery and petrochemical project.

China also continued its use of oilbacked loans to bolster its fuel supply. Resource-backed loans were used to fund infrastructure projects in Angola; oil-sector development in Brazil; finance, education, healthcare and infrastructure projects in Ecuador; road projects in South Sudan; and a variety of infrastructure projects in Venezuela. This arrangement led to a significant uptick in oil imports from Brazil especially, a country which ranks in the top ten oil exporters to China, along with Angola and (until 2020) Venezuela. However, after 2016, Beijing’s priorities were altered by China’s slower economic growth, oil prices persistently below US$75/ barrel (between 2014 and 2021), ensuing repayment challenges in some borrower countries, and the need to green the country’s power generation. Beijing has invested more heavily in renewable energy, and natural gas remains important, especially as a transition fuel as China seeks to reduce carbon emissions, since natural gas emits around half the CO2 produced by burning coal. The impetus for investment in oil – and in coal – has waned. Although high coal and oil prices in 2022 might appear to reverse this rationale, China is well placed to benefit from cheap Russian oil and gas as European countries wean themselves off Russian energy.

China’s gas imports more than tripled between 2012 and 2020, and much of its appetite for gas has been met by the same countries that supply the rest of the world – exporters such as Australia and Qatar. However, China’s pipeline projects have ensured that it does not rely on these countries as much as it might have. Instead, pipelines have allowed China to develop a more diverse supply of gas than nearby Japan or South Korea, with a large share of gas also coming from Turkmenistan, Russia, Kazakhstan and Myanmar. Likewise, during a period when the United States and Canada accounted for some of the biggest additions to the global supply of crude oil, China has secured increased crude-oil imports from Russia, Iraq, Brazil and Oman instead, avoiding the geopolitical risk of importing oil from North America. Again, pipeline connectivity to Russia and infrastructure investments in other countries helped to maintain the diversity of China’s oil imports. By 2021, China was less dependent on energy produced by the West (especially the US and Australia) than it was before the BRI.

However, the majority of China’s oil imports continue to be transported through the Strait of Malacca. China’s ports on the South and East China seas have a capacity of around 15.3 million barrels per day (mbd), whereas its crude-oil pipelines from Kazakhstan, Myanmar and Russia have a capacity of just 1.7 mbd, with some potential for smaller oil shipments via rail or by sea from Russia (through Kozmino port). Therefore, the problems Beijing set out to address have not been fully solved. China’s worldwide role in the energy sector Chinese companies’ expertise in energysector projects carried over into BRI projects that had little to do with China’s own energy security. Many countries participating in the BRI have sought major investment in their own energy sectors, and Chinese investors in those countries often needed a more reliable supply of electricity to support their own activities. As a result, the energy sector was the biggest sector for investments and lending in the early years of the initiative. These loan-financed energy projects in coal, oil, gas, hydropower and alternative energy have earned Chinese companies almost US$200bn in construction contracts since 2014,25 helping companies including China Energy Engineering, China National Machinery Industry Corporation (Sinomach), CNPC, PowerChina and China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation (Sinopec) to establish themselves among the largest power-engineering companies globally. Although Beijing has invested more heavily in renewable energy in recent years, investment in natural gas remains important both because it is a potential bridge fuel, and because China currently relies on Australia, with which it has had a diplomatic falling-out since 2020, for around 25% of its LNG imports.26 This likely explains why, after many delays, CNPC has resumed work on construction of the next phase of the Central Asia–China Gas Pipeline, Line D, which will increase China’s supply of gas from Turkmenistan to the equivalent of 30% of its 2019 imports.

The first mention of what would become the Digital Silk Road came in the March 2015 document ‘Vision and Actions on Jointly Building [the] Silk Road Economic Belt and [the] 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road’, a set of guidelines issued by China’s NDRC, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Commerce that laid the foundation for the BRI. It referred to an ‘Information Silk Road’, which would include the construction of cross-border optical cables and transcontinental submarine cables and improvements to satellite communications, and encouraged investments that ‘strengthen cooperation with overseas high-tech and advanced manufacturing companies, as well as overseas research and development institutions’. The goals coincided with the Chinese government’s ‘Made in China 2025’ (MIC 2025) plan, unveiled in May 2015, ahead of its inclusion in the 13th Five-year Plan in 2016. MIC 2025 set out China’s ambitions for moving from low-value to high-value manufacturing, targeting ten key industries, with the country’s growing information-technology industry first among them. By July 2015, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) had coined the term ‘Digital Silk Road’,30 and the Chinese government fully unveiled the concept at the World Internet Conference in Wuzhen, an annual event organised by the Chinese government, with two sessions on the opening day of the 2015 conference discussing the DSR. But it was the first BRF in 2017 that gave the DSR real political momentum.

At the forum, Xi reiterated the importance of information connectivity and information sharing and proposed to ‘pursue innovation-driven development, to intensify cooperation in frontier technological areas such as digital economy, artificial intelligence, nanotechnology and quantum computing, and to advance the development of big data, cloud computing and smart cities so as to turn them into a digital Silk Road of the 21st Century’. In launching the DSR, the Chinese government was riding on the coat-tails of an already successful Chinese tech sector. By the time the BRI turned its focus to the digital economy, China’s digital-tech firms were already innovating, growing quickly and expanding overseas. Huawei’s and ZTE’s large overseas footprints date back to the early 2000s, when both companies began building telecommunications networks in other countries, from 2G networks on, with support from the Chinese government. In 2004, the China Development Bank had loaned Huawei US$10bn to expand overseas, and in 2012, Huawei was awarded a contract to build a national fibre-optic network in Kenya worth US$60.1m, financed by the Export–Import Bank of China.

But whereas Chinese firms were previously driven by a commercial imperative to expand into new, lucrative markets, once Beijing’s attention turned to the sector, they were co-opted into Xi’s plan to establish China as a ‘digital/cyber superpower’. In this quest, China has pursued the full spectrum of digital projects through the DSR: infrastructure projects (telecommunications networks, submarine fibre-optic cables, overland fibre-optic cables and satellite ground-tracking stations); services projects (smart cities, securityinformation systems and data centres – both cloud-based and bricks-and-mortar); and over-the-top (OTT) projects (platforms for e-commerce, fintech and e-governance). Of China’s 1,758 overseas information and communications technology (ICT) projects, 11% have been OTTs; 37% have been in the services sector (with data centres most common, then security-related projects, then smart-city projects); and around 50% of projects have been in ICT infrastructure.

But as technology has evolved and as BRI countries’ telecommunications infrastructure has modernised, the share of projects in each of these subsectors has evolved. Projects in the infrastructure subsector still dominate, but services and OTTs have accounted for a growing share of the DSR. In particular, the number of e-commerce and fintech investments trended sharply upwards after 2016. An increasingly significant component of the DSR consists of ‘safe city’ or ‘smart city’ projects. These efforts deploy an intelligent network of connected sensors that transmit data to a central authority, which is then used for big-data analytics to improve the quality of life and efficiency of urban environments. These projects generally have a substantial public-security component. Huawei is the leading provider of such projects, which were rolled out in many Chinese cities before becoming part of the DSR menu. China is a leader in biometricidentification systems that underpin smartcity and other public-security-focused projects. These components have become increasingly controversial, especially in authoritarian DSR partner countries, where they are portrayed by critics as important facilitators for the repression of political opposition. It does not appear, however, that China has specifically targeted authoritarian states for these projects, as there has been demand for them across DSR partner countries. Although Chinese companies have significant commercial strengths, Beijing has played an important role in encouraging and supporting the expansion of Chinese tech companies overseas, albeit in a way that differs from how the government supports Chinese firms building power and energy infrastructure.

The DSR’s financial scale and actors are different. Firstly, the cost of digital projects is generally lower than for power and transport projects, especially in the case of services and OTT projects, for which large loans from the Chinese government are not needed. BRI member states that want to procure Chinese firms’ products or services can often afford to do so without Chinese government assistance. Secondly, unlike in the power and transport sectors, private technology companies are dominant, rather than SOEs. That is not to imply that the Chinese government’s support to tech firms through the DSR is unimportant. Perhaps the most conspicuous form of government support is the formal MOUs on digital cooperation signed with BRI member states. Between 2015 and 2020, 16 countries signed DSR MOUs,36 which China has followed up with action plans to roll out DSR projects. Some DSR projects have been negotiated at the heads-of-state level, such as the Konza Smart City project in Kenya.

In some cases, DSR projects have been packaged together with the BRI’s power- and transport-infrastructure projects at both programmatic and project levels. At the programmatic level, CPEC not only connects Pakistan and China by road, rail and gas pipelines but also through the overland fibre-optic cables of the CPEC Fibre Optic Project, which has been in development since July 2018 and involves laying 820 kilometres of cables. At the Chinese-built Karot Hydropower Station in Pakistan, Megvii surveillance cameras have been installed for security on the site. But more broadly, there are few cases of packaging digital- and physical-infrastructure projects together. For some of the largest digital projects, loans from Chinese policy banks have been an important source of finance. Chinese banks have spent nearly US$7bn in loans and investments in cable and telecoms networks. For example, Huawei’s 6,000 km fibre-optic cable across the Atlantic, connecting Brazil and Cameroon, has been financed through a concessionary loan. Much of this Chinese government funding has been directed to low- and lowermiddle-income countries that could not otherwise finance large digital projects. Moreover, China’s tech giants are now well capitalised and more capable of investing on their own. Therefore, in addition to direct Chinese government financing, Beijing promised its tech companies that overseas digital projects (like all BRI projects) would receive favourable arrangements for tax, foreign exchange, insurance and customs clearance.

However, China’s private companies have been somewhat reticent about their role in the DSR. While Huawei refers to the ‘Silk Road’ in several articles on its English website, Alibaba, Huawei and Tencent make no reference to the BRI or the DSR in their annual reports, perhaps trying to avoid Western governments’ animus. By contrast, Chinese state-owned telecommunications companies have promoted the DSR and linked their projects to it. For example, when China Telecom Europe established its new point-of-presence (PoP) data centre in Athens, Greece, in 2019, the firm marketed it as part of its DSR roll-out in Europe. The DSR is bringing Xi’s dreams of China as a cyber superpower closer to reality. Chinese technology firms offer a full ‘tech stack’ (the combination of technologies required to run an application) system on which digital economies depend. Chinese firms offer advanced technology, provide products that solve local problems in the developing world, and do so at low cost. Companies like Alibaba, Huawei and Tencent offer advanced technologies to markets in the developing world and emerging markets that allow them to increase their digitalisation and global connectivity. Alibaba’s biggest foreign market for e-commerce is Southeast Asia, where it operates through a local subsidiary, Lazada; it also has the largest market share for cloud services in the Asia-Pacific, ahead of Amazon and Microsoft. Huawei has brought state-ofthe-art 5G networks to 71 countries around the world. By investing in developing economies which have generally been overlooked by Western competitors, Huawei’s share of the global market for telecoms equipment, at 29%, is nearly equal to that of Ericsson and Nokia combined (17% and 13%, respectively). Huawei has outgrown its earlier reputation for cheap, low-quality hardware.

There is strong global demand for Chinese firms’ digital products and services. The global success of Chinese tech firms, especially in emerging technologies such as 5G, has generated geopolitical and geoeconomic anxiety in the United States and its allies about the DSR. The geopolitical concern is that, although there has been some local pushback against the BRI’s physicalinfrastructure projects, DSR projects have been received positively in key developing regions, especially Southeast Asia, and are helping to forge closer relations between governments there and Beijing. In terms of geo-economics, the US and its allies are concerned that Chinese firms are surpassing Western competitors in key emerging technologies, that the world is becoming overly dependent on Chinese technologies and that Chinese data-privacy standards may become widespread. The US response has been both to press other governments to forgo use of Chinese equipment, especially for 5G networks, and to ban exports of intermediate goods on which China’s supply chains depend. In the medium term, this might threaten Chinese firms’ ability to continue to export their technology to BRI countries. Huawei already finds itself buffeted in strategically important parts of the world. US pressure has also caused some BRI countries to equivocate on DSR projects to avoid antagonising the US. In Europe especially, BRI members Albania, Bulgaria, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, North Macedonia, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia have all decided against using Chinese 5G technologies. So too did Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, which have since disengaged altogether from the BRI. In 2019 and 2020, the number of completed DSR projects dropped dramatically (as was the case with BRI projects more generally), albeit partially because of market saturation.

In the longer term, continued US-led efforts to drive Chinese companies out of the global digital ecosystem could speed up China’s development of indigenous digital technologies (hardware and software alike). If Chinese companies become self-sufficient in digital technologies across the tech stack and export these through the DSR, and if Western competitors fail to extend into developing markets and rebuild their share of the global ICT industry, Chinese tech companies could become dominant players in many developing and emerging markets. US policies are likely to drive China to more aggressively promote its cyber norms globally as well as through the DSR. Altogether, these trends are poised to speed the bifurcation of the digital ecosystem along technological and political lines. In such a scenario, BRI participant states in which there is little or no pushback against Chinese technology will be increasingly important for the Chinese state and Chinese tech companies.

When China announced its Made in China 2025 plan in 2015, its ambitions in advanced manufacturing spanned the digital sector and nine other industries, namely ‘numerical control tools and robotics, aerospace equipment, ocean engineering equipment and high-tech ships, railway equipment, energy saving and new energy vehicles, power equipment, new materials, biological medicine and medical devices, and agricultural machinery’.50 Beijing saw the opportunity to use the BRI to further China’s goals in two of these industries in particular: green technologies, and medical products and services. In 2017, China began to speak of both the ‘Green Belt and Road’ and the ‘Health Silk Road’. As with the DSR, Chinese firms were already establishing a footprint overseas in the green-tech industry before Beijing trained the BRI’s focus on it. In Europe, Chinese firms were installing wind farms in Southeast Europe as early as 2013. In Africa, they were already rolling out locally-funded solar projects as contractors; one of the first such major projects was awarded by the Algerian government to Yingli in 2013. Chinese firms were also making greenfield investments in solar energy in Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam, and China’s first major loan-financed solar-power project came in Kenya in 2016.

Just before the first BRF in May 2017, China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection (now the Ministry of Ecology and Environment) published its ‘Guidance on Promoting [the] Green Belt and Road’. These recommendations were an attempt to deflect criticisms that BRI projects were doing environmental harm and proliferating carbon-intensive power generation. But besides committing to doing less environmental harm, China set out ambitions to ‘boost green infrastructure’ and to ‘advance green trade’, including by expanding China’s exports of green products and services. The BRI would provide markets to complement China’s domestic industrial strategy in green technology. As Beijing directed BRI resources towards green tech, the sector’s overseas expansion took off. The value of Chinese engineering and construction contracts for alternative-energy projects overseas (e.g., solar farms, wind farms, biomass plants, geothermal power plants) doubled in 2017 (excluding hydropower, which has long been an important sector for Chinese lending). The share of Chinese overseas contracts devoted to alternative energy (by value) grew from 1.9% in 2013–1656 to 5.5% in 2017–20. However, unlike in many other sectors, Chinese firms have often been contracted by foreign energy companies to construct alternative-energy facilities, only a modest fraction of which have been financed by Chinese loans. The biggest direct beneficiaries have been Chinese SOEs, with China Energy Engineering, PowerChina, Shanghai Electric, Sinomach and State Grid Corporation of China each winning more than US$1bn in contracts between 2017 and 2020. Chinese greenfield investment in alternative-energy projects overseas also increased from 2017 until the coronavirus pandemic, concentrated in BRI countries.

PowerChina and Shenzhen Energy Group have been the two largest SOE investors overseas in green energy, with Chinese private companies also playing a major role: Sany invested more than US$1bn overseas in 2017–20, and KS Orka invested more than US$500m. These SOEs and private companies are among the world’s largest builders of alternative-energy facilities. The biggest overseas destinations for Chinese investment in alternative energy have been Pakistan (around US$1.5bn), Ukraine (around US$1bn) and Brazil (around US$700m). Additionally, in the United Arab Emirates, solar-farm concessionaire ACWA Power RenewCo – a major Saudi developer in the renewable energy sector which, since 2020, has been 49% owned by China’s Silk Road Fund – has contracted Chinese SOE Shanghai Electric to build the fourth and fifth phases of the Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Solar Park.

Behind the contractors and investors is a supply chain of rapidly growing Chinese manufacturers of green technology, including photovoltaic cells, wind turbines and batteries. China is the world’s largest exporter of photovoltaic equipment, with seven Chinese firms among the world’s top ten photovoltaic manufacturers (by market share) in 2022. In that same year, China was the third-largest exporter of wind-turbine equipment as well, just behind Denmark and Germany, with China’s Goldwind and Envision among the five largest firms.

Unlike in the ICT and green-tech sectors, China only had a small overseas footprint in the health industry before the BRI, with its efforts directed instead at health development assistance (construction of hospitals, donations of equipment and provision of medical expertise) and the promotion of Chinese traditional medicine. But in its 13th Five-year Plan, announced in 2015, Beijing recognised the economic value of developing its health and biotech industry and, in October 2016, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s Central Committee and China’s State Council launched their ‘Healthy China 2030’ strategy. In this plan, Beijing set out ambitions for China to develop its health industry and become a ‘world pharmaceutical power’, with aspirations to make advances in the use of big data and IT in health, genomics technology, stem-cell and regenerative medicine, vaccines, biological treatments, chronic-disease prevention and control, precision medicine and smart medicine, among other aspects of modern medicine. It also highlighted a role for South–South cooperation in developing China’s health industry.

However, when China convened a ‘Belt and Road High-level Meeting for Health Cooperation’ in 2018, the communiqué signed by attending states and international organisations focused on support for traditional medicine, promotion of healthy lifestyles and improvement of environmental conditions, rather than on advanced medicine and health technologies (although Chinese Health Minister Li Bin lauded China’s achievements in these areas at the meeting). In practice, China’s overseas activity remained modest and disconnected from the development of China’s domestic health industry. Little came of the Health Silk Road until the coronavirus pandemic, when China became the main exporter of personal protective equipment (PPE) to the world. China labelled its exports and donations of PPE, and the dispatch of Chinese medical teams overseas, as part of the Health Silk Road. In June 2020, at a videoconference meeting on the BRI, the Health Silk Road took centre stage. The joint statement issued by Beijing on behalf of the participating governments committed ‘to enhancing the availability, accessibility and affordability of health products of assured quality, particularly vaccines, medicines and medical supplies’ and to making ‘investment[s] in building sound and resilient health related infrastructures, including the development of telemedicine’.66 Through the Health Silk Road, Beijing has sought to establish its status as a major producer not only of low-value products, such as PPE, but also of biotechnology (vaccines and medicines) and telemedicine services (which coincide with China’s aspirations in digital services). These ambitions met with early success. Despite the opacity surrounding their development, China deployed several COVID-19 vaccines and tested them in Russia and partner countries in Latin America, the Middle East and North Africa, and South and Southeast Asia. In late 2020, Chinese companies Sinovac Biotech and China National Pharmaceutical Group Corporation (Sinopharm) brought COVID-19 vaccines to market and began to export them widely, despite the fact that Beijing did not make public the testing data for either vaccine. In February 2021, a Chinese government spokesperson claimed that Chinese vaccinations were being donated to 53 countries and exported to 22, although the full list of destinations and quantities remains unclear.

The apparent early success of China’s vaccine development and the low levels of COVID-19 in China enhanced international perceptions of China’s health industry and put Beijing in ‘pole position’ for vaccine diplomacy. But by March and April 2021, China’s COVID-19 response came under considerable international criticism. World Health Organization Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus criticised Beijing’s lack of transparency in the inquiry into the origins of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, calling for more on-theground research. Shortly thereafter, reports from Brazil, Chile and the UAE found that Chinese vaccines were not as effective as many non-Chinese vaccines; and the head of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention issued (but later retracted) a statement suggesting that the Chinese vaccines from Sinopharm and Sinovac do not work as well as other vaccines and that new vaccines or approaches by China may be needed. Therefore, China’s pathway for the Health Silk Road has encountered more obstacles. Post-pandemic, Beijing will certainly look to promote its health industry overseas in much the same way it has promoted digital services. And, as in digital technologies and services, China can fill the vacuum left by Western healthcare companies (including pharmaceutical companies and healthservice providers), which have overlooked or underserved developing countries. But taking advantage of that opportunity will depend on whether China’s health industry can improve its performance in the face of its vaccine setbacks. Chinese firms can provide health products and services more cost efficiently than Western firms, but these need to be seen as safe and reliable.

In advance of launching its ‘14th Five-year Plan’ in 2021, and as part of its new ‘dual circulation’ strategy, the Chinese government undertook two major economic initiatives: ‘China Standards 2035’ and the development of independent supply chains. The BRI has an important role to play in both. The Standardisation Administration of China and the Chinese Academy of Engineering began developing the China Standards 2035 strategy in 2018. Their aim was both to improve China’s standards in a variety of industries and to take the initiative in setting standards for emerging industries and technologies, domestically and internationally. This aim stemmed, in part, from a recognition that China’s influence on international standards was not commensurate with the size of China’s economy or Beijing’s aspirations to become a global power. For Beijing, the lack of influence on international standard-setting was problematic for two reasons. Firstly, Beijing recognised that if international standards aligned closely with the standards used by Chinese firms, then those firms could have a competitive advantage over foreign firms. Conversely, China’s lack of influence on international standard-setting could enable foreign firms and governments to influence standards in ways that disadvantaged China’s leading companies. Secondly, Beijing’s preferences – for example, with respect to state control of the internet, data privacy and surveillance – diverge from those of Western governments and businesses. In these instances, to protect its interests, China has sought to increase its influence in setting international technical standards.

The irony in Beijing’s strategy is that international standard-setting had not previously been an arena for geo-economic competition, but China’s active engagement has made it so. Before China Standards 2035, Beijing had developed two Action Plans on Belt and Road Standard Connectivity. The first, published in 2015, focused on the mutual recognition of standards with BRI members and improvements to China’s domestic standards. The second, published in 2018, began to address the international influence of Chinese standards. In both documents, the emphasis was on standards in long-established industries, including electric power, railways, ships, home appliances, metallurgy and traditional Chinese medicine, rather than in emerging industries, where China could craft a strategic advantage for its national champions. But in his speech at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) conference in November 2020, Xi hinted that the BRI had a bigger role to play in the roll-out of China Standards 2035, pledging that ‘China will further harmonise policies, rules and standards with BRI partners, and deepen effective cooperation with them on infrastructure, industry, trade, scientific and technological innovation, public health and people-topeople exchange’. However, Beijing has yet to lay out exactly what role the BRI can play in international standard-setting.

China’s next action plan on standards with BRI members is likely to focus on priority industries identified in the Standardisation Administration of China’s Main Points of National Standardisation Work in 2020. Among the priorities are ‘blockchain, the Internet of Things, new cloud computing, big data, 5G, artificial intelligence, smart cities, and geographic information’. Both by selling Chinese technologies to BRI member states (especially to partner governments) and by elevating the importance of the ‘policy coordination’ pillar of the BRI, China will look to influence the preferences of partner governments in regard to international standard-setting. Given the emphasis on advanced technologies, which are less relevant to the poorer countries in the BRI, the main targets for regulatory influence will be the more economically advanced members, with a particular emphasis on Southeast Asia. Southeast Asia will also be the focus of China’s efforts overseas to strengthen its supply-chain security. As discussed earlier, growing competition with the US has exposed China’s vulnerability to external risks. Of particular concern to Beijing is the tightening of US export controls that have prohibited Huawei from acquiring semiconductors made with US technologies, thereby cutting its access to virtually all high-end products in the field. Likewise, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation, China’s leading chipmaker, is restricted from buying USorigin equipment essential for its operation. These sanctions not only pose existential threats to leading Chinese technology companies but also call into question the viability of China’s development model if its relationship with the West remains fraught.

Beijing recognises that if economic growth and its national champions become over-reliant on markets and critical inputs from abroad, China’s economic security will be at risk. In response, the Chinese government has set self-reliance in critical supply chains as a national priority. In April 2020, the Politburo Standing Committee, the most senior CCP decision-making body, set out its ‘dual circulation’ strategy for China’s economy, which would see Beijing reduce its dependence on both foreign markets and supply chains. Through domestic innovation and import substitution, Beijing seeks to insulate Chinese supply chains from external pressures. It will also look to rely less on those Western markets where there are growing political risks to Chinese trade and investment. It is a more inward-looking approach that echoes China’s protectionist industrial policies of the past. Xi stated that China needs to build independent supply chains to protect national security under extreme conditions. Vice Premier Liu He was directed to work with different industries to identify ‘choke point’ technologies vulnerable to US sanctions.

At the 2020 Central Economic Work Conference, the Chinese leadership called for a ‘ten-year action plan’ for basic scientific research to support the development of core technologies. Taken together, these initiatives point to an enlarged role for the state sector, despite its inadequacies when it comes to technological innovation. Besides strengthening domestic supply chains, Beijing’s strategy seeks to build international supply chains that depend on Chinese technologies. Beijing intends to increase other countries’ reliance on China through the export of technological goods and services, and through collaboration within the BRI on related technology. In Xi’s April 2020 speech, he also stressed the importance of reinforcing China’s advantage in fields such as high-speed railway, power equipment, renewable energy and telecommunications. In his own words, having a few technological ‘winning cards’ would allow China to ‘deter and counter others’ coercion’. According to the 14th Five-year Plan, the BRI is expected to help China and BRI partner countries build ‘mutually beneficial industrial supply chains’. In the latest Five-year Plan, Beijing also added to its ambitions for the BRI new technology elements, including a ‘scientific innovation action plan’, and emphasised that the DSR would continue to be a key component of the BRI going forward. These ambitions are not yet manifest in BRI projects, but look to shape the initiative in future.

Since its launch in 2013, the BRI has served Beijing’s geopolitical ambitions, as well as its economic objectives, as China has sought to increase its influence around the world. As commentaries in Chinese state media have argued, the economic downturn in the West following the 2007–09 global financial crisis presented China with an opportunity.78 By bringing more countries into its economic orbit and establishing itself as a leading actor in global economic development, Beijing believes that BRI partner countries will more likely act in line with the geopolitical interests of China. However, the changing context of China– US relations has profoundly shaped Beijing’s approach to achieving this goal. During the early years of the BRI, Beijing’s strategy was simply to deepen its relationships with foreign governments and establish China as one of their main economic partners through a campaign of lending, investment and summitry. But Beijing avoided diplomatic ventures that might lead to direct confrontation with the United States. This influenced the geography of the BRI in its early years, until around 2019. During the Obama administration, the US was preoccupied with exiting wars in the wider Middle East. While Obama initially sought to negotiate the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) with 11 Pacific states, fear of congressional rejection led the administration to drop the initiative. Meanwhile, in the years immediately before and after the launch of the BRI, Beijing focused its diplomatic attention on countries where the US was less politically invested, including states in Southeast Asia, Central Asia, South Asia, Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa. The economic corridors that were at the heart of the BRI in its early stages traversed these regions.

The economic corridor in Pakistan, CPEC, was a prime example of Beijing’s approach. During the United States’ war against al-Qaeda and the Taliban in Afghanistan, Pakistan was a critical partner for the US, especially as a transport and staging area. In turn, the US provided Pakistan with vast sums of military and development aid. Exasperated by the support given by parts of the Pakistani state to the Taliban and by corruption and misallocations of funds, the US scaled back its support for Pakistan from 2014 and China stepped into the breach (for further details, see ‘South Asia’ chapter). However, as much as Beijing avoided confrontation with the US at this time (until around 2019), it pushed hard to isolate Taiwan. Taiwan’s pursuit of autonomy from the mainland – a relic from China’s unfinished civil war – remains a continuous affront to Beijing. The BRI has been one of its main instruments (though not its most important one) to push governments that maintain diplomatic relations with Taiwan to drop these ties and instead to engage with – and accept loans and investment from – Beijing. As of 2022, only 14 countries officially recognise Taiwan, with most based in Latin America and the Caribbean. Virtually all nations that have shifted recognition from Taiwan to China in the past decade are BRI recipients.

Moreover, although the overall emphasis of the BRI has been on deepening relationships with partner countries – through influence and soft power – there has been a significant, though implicit, coercive and geo-economic dimension to China’s economic diplomacy too. China’s emergence as the pre-eminent lender to developing countries has led partner governments, with few exceptions, to avoid antagonising Beijing. And China has knowingly used the leverage it has accumulated through trade, lending and investment through the BRI to pressure foreign governments, both quietly and (especially since 2020) less quietly, to pursue policies that are to its liking. At the United Nations, this new leverage has helped China to corral other states into temporary coalitions of countries to oppose specific measures, particularly those sponsored by the West, that are critical of China. And in Europe, participation in the BRI has led several European Union members to block or water down policies that are critical of Beijing .

The geography of the BRI changed over time as China’s path for avoiding competition and confrontation with the US has narrowed. As much as Beijing tried to avoid confrontation, Washington became increasingly nervous about China’s growing influence around the world and the challenge it presents to American hegemony. In turn, China has become more open about its competition for influence with the US. In particular, China’s outreach to traditional US allies in the Gulf has grown. And China has leapt at the opportunity presented by the US withdrawal from the TPP to take the lead on economic diplomacy in the Indo-Pacific region, focusing more of its lending and investment there, and negotiating the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) with the members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea. And, in 2021, China took advantage of the United States’ absence to apply to join the successor trade agreement to TPP, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

The BRI has evolved to accommodate Beijing’s growing economic ambitions and will continue to evolve to serve new objectives. Although China’s lending and investment in energy and transport infrastructure has slowed, other aspects of the BRI continue apace and are accelerating. As China’s domestic economic strategy focuses now on dual circulation, the BRI will adapt to ensure Chinese economic activity overseas supports Beijing’s ambitions for supply-chain security and for reduced reliance on Western markets. In this way, the BRI serves as a flexible platform for China’s developmental engagement with its BRI partners in their dozens, as well as a vehicle for China’s own developmental objectives. As Beijing’s priorities have changed, so has the relative importance of the different BRI regions. When China’s concerns were first and foremost about energy security and trade connectivity with Europe, its economic corridors towards the west, to Central Asia, the Middle East and Europe, were at the centre of the initiative. But increasingly, Southeast Asia is central to its priorities. While China has demonstrated that there is a market for digital technologies in the developing countries of Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, it is pressing more and more into advanced industries (and standard-setting in these industries), where Southeast Asia is the most attractive destination. Moreover, Southeast Asia has the most promising role to play in strengthening China’s supply chains for advanced technologies.

Taken from the IISS Strategic Dossier China's Belt and Road Initiative, November 2022.