The connections between China and Central Asian nations such as Kazakhstan are garnering a lot of attention lately. News media are reporting that this May Xi’an in China will play host to the first in-person Central Asia-China Summit. Kazakhstan and China are known to be discussing the possibility of dropping visa requirements for travelers between the two countries, Astana Times reports.

Kazakhstan, along with other countries in Central Asia, has a long and complex history with the nation of China. The countries have enjoyed fruitful economic cooperation, and there is still a lot of work to do on a path to strengthen our relations.

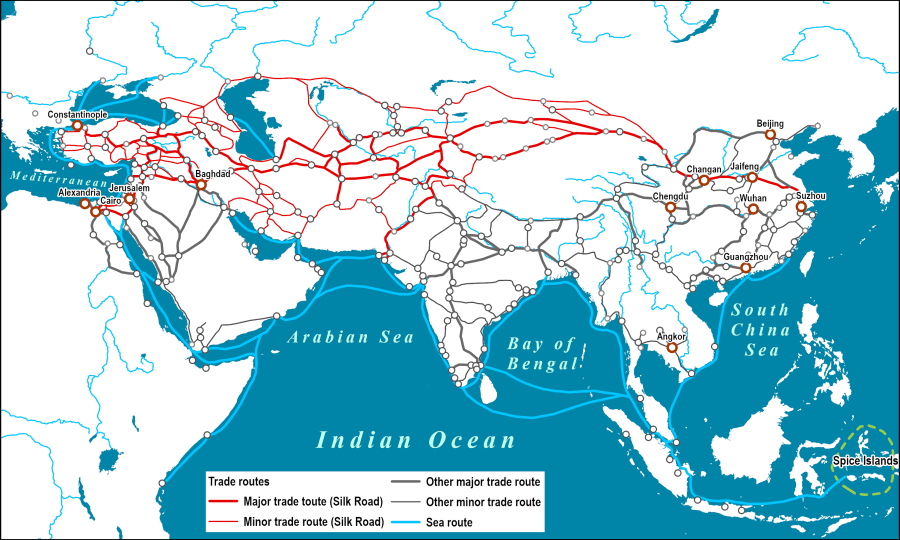

The Silk Road consisted of a succession of trails followed by caravans through Central Asia, about 6,400 km in length. Travel was favored by the presence of steppes, although several arid zones had to be bypassed such as the Gobi and Takla Makan deserts. Economies of scale, harsh conditions, and security considerations required the organization of trade into caravans slowly trekking from one stage (town and/or oasis) to the other.

Although it is suspected that significant trade occurred for about 1,000 years beforehand, the Silk Road opened around 139 BCE once China was unified under the Han dynasty. It started at Changan (Xian) and ended at Antioch or Constantinople (Istanbul), passing by commercial cities such as Samarkand and Kashgar. It was very rare that caravans traveled for the whole distance since the trading system functioned as a chain. Merchants with their caravans were shipping goods back and forth from one trade center to the other. In addition to silk, major commodities traded included gold, jade, tea, and spices. Since the transport capacity was limited, over long distances and often unsafe, luxury goods were the only commodities that could be traded. The Silk Road also served as a vector for the diffusion of ideas and religions (initially Buddhism and then Islam), enabling civilizations from Europe, the Middle East, and Asia to interact.

The initial use of the sea route linking the Mediterranean basin and India took place during the Roman Era. Between the 1st and 6th centuries, ships were sailing between the Red Sea and India, aided by summer monsoon winds. Goods were transshipped at the town of Berenike along the Red Sea and moved by camels inland to the Nile. From that point, riverboats moved the goods to Alexandria, from which trade could be undertaken with the Roman Empire. These trade routes have also been instrumental in the spread of diseases and the first pandemics. For instance, the Justinian Plague of 541 (a form of bubonic plague) is believed to have spread to the Mediterranean from its East Asian origins through trade routes.

From the 9th century, maritime routes controlled by Arab traders emerged and gradually undermined the importance of the Silk Road. Since ships were much less constraining than caravans in terms of capacity, larger quantities of goods could be traded. The main maritime route started at Guangzhou, passed through Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, and then reached Alexandria. A significant feeder went to the ‘Spice Islands’ (Maluku Islands) in today’s Indonesia. They were named as such because spices such as nutmeg, mace, and cloves could initially only be found there.

The Silk Road reached its peak during the Mongolian Empire (13th century) when China and Central Asia were controlled by Mongol Khans, which were trade proponents even if ruthless conquerors. At the same time relationships between Europe and China were renewed, notably after the voyages of Marco Polo (1271-1292). The diffusion of Islam was also favored through trade as many rules of ethics and commerce are embedded in the religion.

During the Middle Ages, the Venetians and Genovese controlled the bulk of the Mediterranean trade which connected to the major trading centers of Constantinople, Antioch, and Alexandria. As European powers developed their maritime technologies from the 15th century, they successfully overthrew the Arab control of this lucrative trade route to replace it on their own. Ships being able to transport commodities faster and cheaper marked the downfall of the Silk Road by the 16th century.

Although the ancient Chinese Empire as a whole was not influenced greatly by the Mongol and Turkic tribes from Central Asia, it was in order to protect against raids by these tribes that China built its most famous barrier, the Great Wall. Despite being afraid of potential aggression from Eurasian nomads, imperial China always had a huge economic interest in the region that is now home to the Central Asian countries. For example, the Han Dynasty’s expansion into Central Asia laid the foundation for the famous Silk Road network that contributed to the economic and cultural exchange between east and west.

The possibility of a new type of Silk Road has been raised by a large-scale building project China is undertaking, known as the Belt and Road initiative. In introducing the One Belt, One Road initiative, as it was called originally, in Astana, Kazakhstan in September 2013, China’s president Xi Jinping stressed that more than 2,100 years ago, during China’s Western Han Dynasty (206 BC – AD 24), an imperial envoy named Zhang Qian went twice “to open the door” to the Central Asian territories in order to develop trade contacts with Central Asia. This led not only to trade between the nations but also served as a pathway to the west for China, facilitating trade with Europe.

The idea of recreating the Silk Road initiative actually was first explored by Chinese Prime Minister Li Peng on his famous goodwill trip to Central Asia in 1994. During that visit, Li Peng proposed the idea of the “Recreating the Silk Road Initiative.” According to an April 20, 1994 article in the International Herald Tribune, Li Peng said, “in the past, the Silk Road joined China and Uzbekistan together… Now we want to build a new Silk Road.”

Since Li Peng’s tour, relations between China and the Central Asian countries have greatly improved and expanded, especially in the areas of economic and trade cooperation. A significant portion of that trade has occurred between China and Kazakhstan, aided by their shared border. But while economic cooperation flourishes, issues between the nations do remain. Political and security concerns are part of the considerations in the relations between Central Asian republics like Kazakhstan and their powerful neighbor.

It should be noted that since becoming independent countries a little over thirty years ago, Kazakhstan and other Central Asian republics have received increased attention not only from China but also from the United States. While the U.S. was very active in the region, even before the Central Asian countries acquired their official independence, its influence is secondary to that of China’s.

This is due, in a large part, to the geographical distance between the region and the United States. This remoteness keeps the United States from committing a large enough amount of resources for full economic engagement with the Central Asian republics. It also limits how much the U.S. can get involved with upgrading the physical infrastructure of these countries. China, in contrast to the United States, is an immediate neighbor to three Central Asian countries: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. This close proximity and the accelerating economic engagement between China and Central Asia sets a new tone in the region. It also calls for new approaches by the world’s superpowers to pursue diplomatic relations in the region.

This new era in relations between China and Central Asia and the need for innovation in diplomacy were amongst the topics considered at an informative dialogue organized by the Caspian Policy Center (CPC) in Washington, DC on April 4.

The Central Asian region, of course, includes Kazakhstan, a nation with an ancient history tied to China and a current economic reality very much still connected to that nation. A huge amount of trade flows between China and Kazakhstan, making it a notable partnership in the area, a partnership with roots that reach far back.

The Kazakh steppes were one of the major hubs along the Silk Road. According to the well-known Kazakh historian Karl Baipakov, even before the Zhang Qian’s missions into Central Asia, the Saka state in the Aral region and the Zhetysu region (a historic region located west of the Tianshan mountain range that forms the border between China and Central Asia) established their own close contacts with China.

Following the diplomatic expeditions by Zhang Qian, the economic and cultural exchanges between China and Kazakhstan (as well as other Central Asian states) intensified. Over the centuries, the relationships amongst all of these countries have turned into a complex interplay of ideological, political and economic factors.

This complex history provides a backdrop to the very modern discussion hosted by CPC with experts exploring China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Central Asia. This initiative is one of the largest and most significant projects China has ever undertaken. The CPC event provided a platform for participants to exchange thought-provoking insights on the implications, opportunities, and risks that this immense Belt and Road program of construction brings to the region.

According to Robert Daly, the Director of Wilson Center’s Kissinger Institute on China and the United States, “China has a relatively easy task in the region.” He stressed that “by virtue of its geography, the attraction of its markets, its status as a number one trade partner in the region, and its offering of connectivity, China has advantages.” These advantages are ones which “the United States cannot match and cannot overcome.” And “that is likely to remain true for a very long period of time.”

Another point made by Daly was that “China does not have to follow through on all of its promises in Central Asia to be able to dwarf the United States’ involvement and contributions to Central Asia.” According to Daly, China’s “emphasis on development, its status as a market for energy, its interest in agriculture and water projects, all dwarf what the United States is actually able to bring to the table.” Daly sees the potential for the U.S. to worsen its standing in the area if it keeps on a path of relating “through its framework of great power competition” and “ignoring all of the parts of the world which are not great powers.” And that is “precisely the areas”, according to Daly, where “China is making inroads.”

The fact that China is “making inroads” in the Central Asian region in terms of increasing its military presence there was underlined by Brianne Todd, a Professor of Practice for the Near East South Asia Center for Strategic Studies at the National Defense University. She pointed out that while infrastructure development projects in Central Asia are slowing, China’s security forces, by contrast, are expanding their involvement in the region. And “they do a lot of different functions” there, “from security patrolling” to “counterterrorism” and “peacekeeping operations.”

Johannes Linn of the Brookings Institution outlined that there is a debt issue involved with the project. Countries face downsides related to natural resources extraction, owing to “unfair and non-transparent revenue sharing.” Another concerning issue relates to the nature of the infrastructure projects themselves. Questions were raised as to whether the Belt and Road initiative targets “the soft” part of infrastructure such as border crossing, improving logistics that would actually “deliver improved services” for China itself. According to Linn, the big issue is whether the transportation infrastructure is “biased towards China rather than to the remaining neighbors and world markets.” Linn also suggested that Central Asian countries involved in infrastructure projects with China should also consider the security of telecom investments made by China and the need for environment protections related to the projects.

While there are notable concerns for the Central Asian countries, there are also concerns in the region for China, too. Elizabeth Wishnick, a Senior Research Scientist for China Studies at the Center for Naval Analyses pointed out that Central Asia “is not just a land of opportunity, this is an area of risk.”

The CPC discussion served as a useful reminder of how challenging a potentially beneficial partnership between Central Asia and China can be. In addition to the many economic issues and security concerns, there is a history of distrust that must be overcome.

Economic cooperation, especially under the Belt and Road Initiative, has the potential to be a turning point in the relations between China and Central Asia. It will hopefully bring about positive, tangible results for the region and balance out the great power competition for influence in Central Asia. Perhaps future historians will look back on the Belt and Road Initiative as the true second Silk Road, bringing connection and prosperity to both ends of its route.

By Assel Nussupova on May 3 2023 for the Astana Times, additional information and map taken from Jan Mansson.