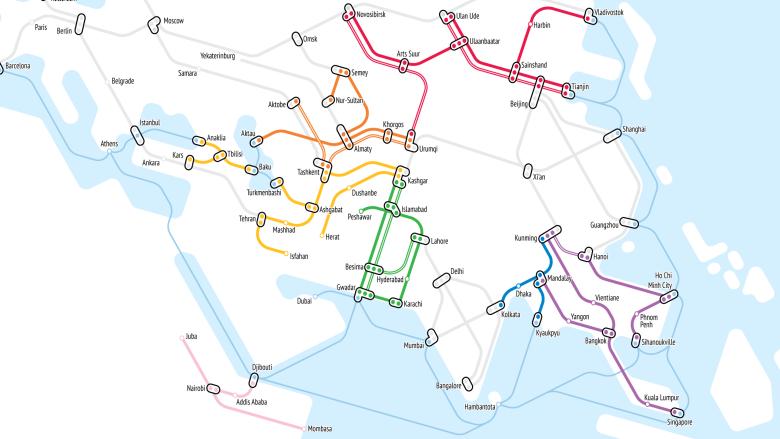

In fall 2013, President Xi Jinping introduced the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) during his visits to Kazakhstan and Indonesia. The initiative aims to revive ancient Silk Roads by encouraging new trade and improving connectivity. The Belt is the land-based “Silk Road Economics Belt” that connects China and Europe through Central Asia and the Russian Federation. The Road is the oceangoing “Maritime Silk Road” that connects China with Southeast Asia, East Africa, the Middle East and ultimately the heart of the Mediterranean. The initiative includes 72 countries around the Belt and the Road and at the moment covers over 60 percent of global GDP and 70 percent of the world population.

The key element of the Belt & Road Initiative is infrastructure investment that improves connectivity and encourages trade and investment across BRI countries. During the Belt and Road Summit in May 2017, the joint communique stated a list of cooperation objectives of BRI. Among many, the two most important objectives are 1) to strengthen physical, institution and people-topeople connectivity among BRI countries; and 2) to expand economic growth, trade and investment. The communique envisions the future of BRI countries to be a win-win situation by creating “prosperous and peaceful community with shared future.

In recent decades, foreign direct investment (FDI) flows as a share of GDP have more than doubled in both developed and developing nations. While developed countries still account for over 70 percent of the world’s outward FDI flows, developing countries including China have become an increasingly important source of FDI. When comparing the distribution in 2001 with the distribution in 2012, we observe a rightward shift along the distance axis; for example, the share of FDI concentrated at less than 2,500 km has fallen from around 40 percent to less than 30 percent. This change suggests an expansion of FDI flow across space in an era when transportation costs have sharply declined.

Reductions in transportation costs could influence FDI through a variety of different mechanisms and the effect evolves with the integration and sourcing strategies of multinational firms. First, the nature of the effect depends critically on the specific motives to invest abroad. While high transportation costs may motivate firms to replicate production across countries (an activity referred to as horizontal FDI), reduction in transportation costs will allow firms to better exploit crosscountry cost differences and engage in vertical or complex FDI strategies where multinational firms separate their production stages across countries and engage in extensive intra-firm trade. In the latter case, FDI and trade become positively interdependent and FDI growth can boost both export and import growth. Second, as FDI involves not only the flow of goods and inputs but also the flow of information, there is an important interplay between investment flows and the flows of ideas and knowhow. Finally, reduced regional transportation costs to transmit goods, intermediate inputs, and services could foster growth of regional value chains. The above effects could, however, vary significantly across countries depending on countries’ business environment and absorptive capacity.

An extensive volume of empirical literature in international trade has examined the patterns of FDI as a function of country characteristics including market size, factor endowment, transportation cost, tariff, and other factors such as corporate tax, institutional quality and exchange rate. The literature shows that the relationship between transportation cost and FDI varies sharply with the nature and type of investment, in particular, between horizontal and vertical/complex FDI. To measure transportation cost, distance or a ratio of cost, insurance and freight (cif) relative to free-onboard import value has usually been used while it is widely acknowledged that distance could capture not only various forms of geographic friction including the costs of communication and monitoring but also other factors such as cultural distance and historical ties. The first stream of studies presents evidence that is in alignment with horizontal FDI by showing a positive relationship between FDI on the one hand and market size and trade cost on the other. Brainard (1997), one of the first empirical studies examining the proximity-concentration trade-off, finds that the patterns in which country characteristics relate to U.S. FDI are broadly in alignment with the market access motive. Specifically, she uses U.S. trade and affiliate sales data from the 1989 BEA Benchmark Survey of U.S. Direct Investment Abroad and finds that FDI increases with hostcountry income and trade cost including the transportation cost to ship goods between the headquarters country and the host country, consistent with the market access motive in horizontal FDI.

The economic impacts of FDI have been studied in a large body of literature, through macro, crosscountry analysis as well as micro, firm-level research. At the macro level, numerous studies have examined the relationship between FDI and economic growth. Evidence suggests that FDI could exert a positive effect on economic growth when host countries meet certain economic conditions, including sufficient human capital stock and relatively developed financial markets. At the firm level, an extensive volume of research has examined the effects of FDI on host countries in a variety of dimensions including productivity, employment, wage rate, and export performance. The productivity effect of FDI, in particular, has attracted considerable empirical attention. In this sub-section, we discuss the literature evaluating the impacts of inward FDI in the context of BRI countries. The literature presented here is based primarily on analysis of historical FDI data in OBOR countries prior to the OBOR initiative.

An extensive empirical literature assesses the existence of productivity spillover from multinational to domestic firms. Such spillover could occur to domestic firms acquired by foreign multinational firms, domestic firms competing with the foreign multinationals, as well as those sharing vertical production linkages.

The impacts of foreign acquisition on targeted firms have been shown in terms of wage premium, employment growth, and productivity increase. In terms of wage premium, Lipsey and Sjholm (2004) use Indonesian manufacturing firm-level data to show that foreign firms tend to hire more educated workers and pay a wage premium even

In addition to transportation and infrastructure data, we also obtain information on FDI regulations and trade and investment agreements. To measure FDI regulations across countries, we use the Investing Across Borders data set, which compares FDI laws and regulations across 87 economies. It presents quantitative indicators on economies' laws, regulations, and practices affecting how foreign companies invest across sectors, start businesses, access industrial land, and arbitrate commercial disputes: Specifically, it includes the following indices:

· Investing Across Borders: its offers measures of statutory restrictions on foreign ownership of equity in new investment projects (greenfield FDI) and on the acquisition of shares in existing companies (mergers and acquisitions).

· Starting a Foreign Business: it quantifies the procedural burden that foreign companies face when entering a new market. It comprises 3 components measuring the time needed, procedural steps required, and regulatory regime for establishing a foreign-owned subsidiary.

· Accessing Industrial Land: it quantifies several aspects of land administration regimes important to foreign companies seeking to acquire land for their industrial investment projects, including the strength of land rights, the scope of available land information, and the process of leasing land in a country’s largest business city.

· Arbitrating Commercial Disputes: it reflects different aspects of domestic and international arbitration regimes in each country applicable to local and foreign companies, including the strength of the legal framework for alternative dispute resolution, rules for the arbitration process, and the extent to which the judiciary supports and facilitates arbitration.

A few patterns emerge from the data. First, in terms of foreign ownership restrictions, BRI countries, on average, are more restrictive than non-BRI countries and high-income OECD countries. Moreover, the degree of openness varies across sectors: service sectors such as construction, tourism, retail, media, banking, insurance and telecom tend to see more restrictions in BRI countries than in non-BRI or high-income OECD countries. Second, BRI countries, on average, impose more restrictions and burdens than OECD high-income countries on starting a foreign business, accessing industrial land, and arbitrating commercial disputes. The gap from high-income OECD countries is particularly pronounced. For example, while the ease index of starting a foreign business is around 80 in high-income OECD, it is around 70 in BRI countries.

Third, when comparing the top 10 and bottom 10 BRI countries in FDI policy, we observe a large heterogeneity within BRI as shown in Tables A.6-A.9. For example, it takes around 16 days to lease land in the Philippines, but more than two-thirds of a year (259 days) to lease land in Afghanistan. While Georgia fully opens all its sectors to foreign investment, Thailand only scores 52 in the openness index.

Finally, we obtain data on several key country-level economic variables for evaluating the impacts of FDI, including, for example, productivity, employment, wages, and exports. Sources for these variables include Conference Board’s Total Economy database, International Labor Organization’s ILOSTAT database, and World Development Indicators. To examine the determinants of FDI inflow into BRI countries, we also obtain country characteristics such as GDP, GDP per capita, infrastructure, human capital (host and source country difference in secondary school enrollment), and institutional quality, all of which are available from the World Development Indicators (WDI). Gravity variables including, for example, distance, contiguity, and language are available from CEPII’s GeoDist database. Lastly, industrial level skill intensity is obtained from NBER-CES Manufacturing Industry Database.

As in earlier studies, transportation costs between source and host countries are found in general to reduce FDI, but the effect varies significantly by the mode of transportation. A 1-percent increase in air distance is associated with 0.7-1 percent decrease in the volume of FDI. Land transportation cost, measured by either driving distance or driving time, is also found to exert a significant and negative effect: a 1-percent increase in driving time, for instance, leads to a close to 1-percent decrease in FDI. In contrast, the effect of sea distance is weaker (insignificant in some specifications): a 1-percent increase in sea distance is related to around 0.1- percent decrease in FDI flows.

Infrastructure quality is found to matter: the results show a significant and positive relationship between each of the three infrastructure quality measures, namely, railway, airway and port qualities, and FDI inflows. Countries with higher railway and airway indices and better ports tend to attract a greater volume of FDI. For example, improving the level of railway index from BRI countries (11.8) to the level of high-income countries (18.5) is associated with 4.3 percent increase in FDI flows. Logistics performance of the source-host pair is also found to be matter: a one-percent increase in the logistics performance index leads to 0.1 to 0.2 percent increase in FDI flows.

A reduction of 29 driving time is found to have the strongest positive effect on FDI in Middle East and North Africa followed by Europe and Central Asia and no significant effect in East Asia Pacific, South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Longer railway is found to have a significant positive effect in South Asia and Middle East and North Africa, but not in the other regions. A better airway index significantly attracts more FDI in East Asia Pacific and Europe and Central Asia, but not in the other regions. The effect of port quality is found to be the strongest for Sub-Saharan Africa, albeit statistically insignificant, followed by Middle East and North Africa and South Asia.

Based on the above empirical results, we now estimate the impact of BRI on countries’ ability to attract FDI by reducing transport costs and improving host-country infrastructure. The elasticity of FDI with respect to driving time estimated for BRI host countries, suggest that a 10-percent decrease in driving time between host and source countries could increase FDI flows by 12 percent. Specifically, a 10-percent decrease in driving time could increase intra-BRI FDI flows by about 11.7 percent, FDI flows from OECD by 13.4 percent, and FDI flows from all non-BRI countries by 9.1 percent. If an improvement in road quality reduces unit driving time in BRI countries to the average level in Europe and Central Asia, total FDI inflow in BRI countries could increase by about 3.6 percent, with 3.5 increase in intra-BRI FDI flow, 4 percent increase in FDI from OECD countries, and 2.7 percent increase in FDI from all non-BRI countries. The results also suggest that improving the port quality from the current BRI country level (4.1) to the level of high-income countries (5.3) would lead to 10-percent increase in total FDI inflow, 10- percent increase in FDI from OECD countries and 12-percent increase in FDI from non-BRI countries. The effects on intra-BRI FDI are statistically insignificant.

In general, the effects of FDI are found to diminish with country income level and the strongest for low-income countries. For example, a 10-percent increase in FDI inflow is found to be associated with 0.45 percentage-point increase in GDP in low-income countries, 0.2 percentage-point increase of GDP in lower-middle-income countries, and 0.08 percentage-point increase of GDP in upper-middle-income countries. The GDP effect in high-income countries is found close to 0 and statistically insignificant. This could be due to the ambiguous effect of M&As, the main type of FDI in high-income countries, on GDP and employment growth. The effect of FDI on import is more pronounced and as the GDP effect diminishes with income level. A 10- percent increase in FDI inflow is shown to raise imports by 1.78 percent, 1.3 percent, 0.7 percent, and 0.3 percent in low-, lower-middle-, upper-middle-, and high-income countries, respectively.

Similarly, FDI exerts a strong effect on exports, especially for lower-income countries. The positive impacts of FDI on trade are consistent with the growing prevalence of vertical FDI and global value chains which leads trade and FDI to co-move in the same direction. The stronger effects on lower-income countries are also consistent with the expectation that vertical FDI and subsequently intra-firm trade are more likely to occur between high- and low-income countries because of their complementarity in task comparative advantage. While the employment effect of FDI is generally insignificant, we find the effect to follow a similar pattern with a greater positive effect on lower-income countries.

To assess the effect of BRI on economic growth through the channel of foreign investment, we combine the estimation results from the two stages. If BRI reduces driving time between host and source countries by 10 percent, FDI flows into BRI countries are estimated to increase by 12 percent and the 12-percent increase in FDI inflow is estimated to raise GDP growth rate by 0.2 percentage point for BRI countries as a whole. But the effect is estimated to be around 0.5 percentage point increase in GDP growth rate for South Asian BRI countries and 0.35 percentage point increase in GDP growth rate for East Asia & Pacific and Middle East & North Africa BRI countries.

If an improvement in road quality reduces unit driving time in BRI countries to the average level in Europe and Central Asia, total FDI inflow in BRI countries could increase by about 3.6 percent and GDP growth rate in BRI countries is estimated to increase by 0.06 percentage point. The effect again is estimated to be strongest (around 0.16) for South Asia BRI countries. Improving the port quality from the current BRI country level (4.1) to the level of high-income countries (5.3) would lead to 10-percent increase in total FDI inflow and 0.17 percentage point increase in GDP growth rate in BRI countries. Across regions, the effect on GDP is estimated to be around 0.45 percentage point in South Asia, 0.3 percentage point in East Asia & Pacific and Middle East & North Africa, and negligible in Europe and Central Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

If the proposed BRI transportation network leads to an average 0.69 shipping day reduction, based on the upper bound estimates from de Soyres et al (2018), our analysis suggests that the improved transportation network can raise BRI countries’ GDP growth rate by 0.09 percentage point through the FDI channel. Across regions, the transportation network is estimated to increase GDP growth rate by about 0.08 percentage point in East Asia & Pacific, 0.04 percentage point in Europe and Central Asia, 0.01 percentage point in Middle East & North Africa, 0.13 percentage point in South Asia, and 0.23 percentage point in Sub-Saharan Africa, as shown in Figure 23.

It is noteworthy that the BRI transportation network can also stimulate growth in non-BRI countries through a spillover effect of the transportation network. For example, non-BRI countries in Sub-Saharan Africa may also benefit from access to ports in Kenya and consequently attract more FDI. Our analysis suggests that such spillover is significant in Africa; non-BRI Sub-Saharan African countries are estimated to see a 3.98 percent increase in FDI inflow with the BRI transportation network and, through the increase in FDI, a 0.13 percentage-point increase in GDP growth.

First, initiatives improving physical infrastructure such as BRI can stimulate FDI growth and subsequently GDP and trade growth, but the effects of FDI on aggregate productivity and innovation are insignificant. Second, the impacts vary significantly with host- and source-country development level, across types of infrastructure, and over time. Investment allocation should take into account the great heterogeneity in the expected returns across different projects and geographic areas. Third, the positive effects of infrastructure investment can be magnified when accompanied with an improvement in business environment, specifically an improvement in the ease of business entry. Fourth, there exists a significant amount of missing FDI, i.e., unrealized FDI potential, across countries. Market size and unobserved institutional factors play a central role in explaining missing FDI, especially for developing countries.

Taken from Foreign Investment across the Belt and Road Patterns, Determinants and Effects by Maggie Xiaoyang and Chen Chuanhao Lin, posted on November 27 2024 by the World Bank. Image