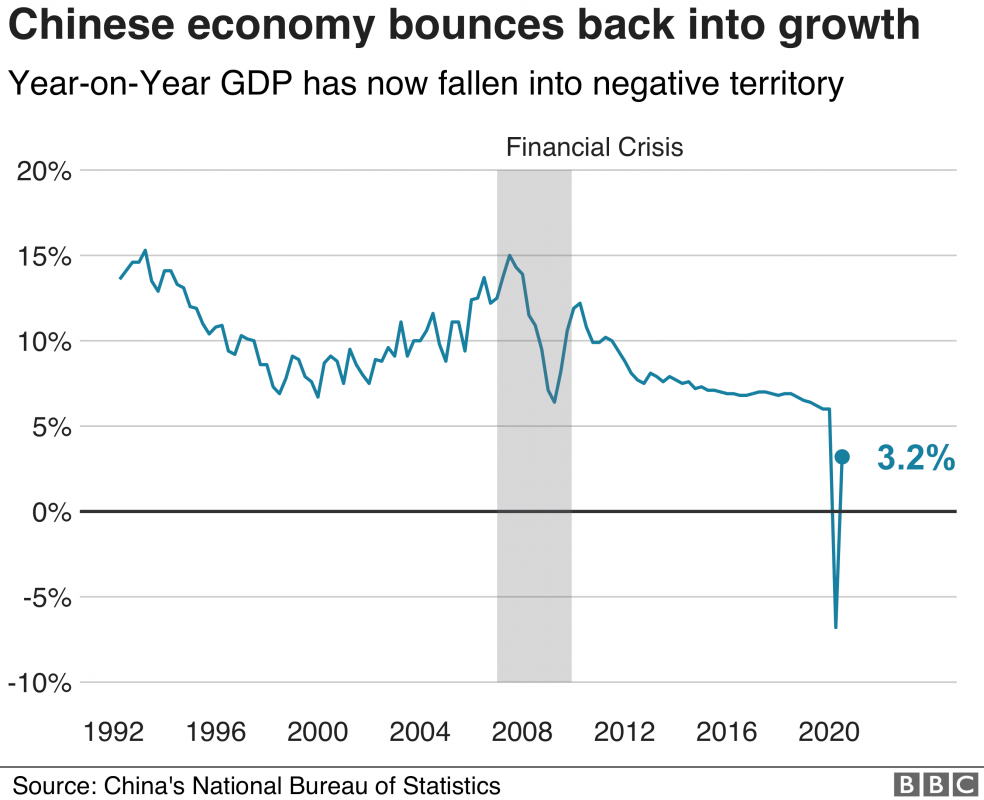

China and the United States signed their long-awaited phase one trade deal in January, somewhat ending their 18 month trade war, but 2020 was dominated by the impact of the coronavirus. As a result, China’s economy shrank by 6.8 per cent in the first quarter of 2020, although it is set to be the only Group of 20 nation to post positive economic growth this year.

With the severity of the coronavirus still unknown, January will be remembered for China and the US signing their long-awaited phase one trade deal.

This included a commitment to buy an additional US$200 billion worth of goods and services over the coming two years.

While the virus had not yet spread into the global pandemic that it would become, we also looked at Wuhan, the hub of transport and industry for central China, which had been sealed off to contain the spread of the deadly outbreak.

Revelations about Canadian extradition proceedings of Huawei Technologies Co. chief financial officer Meng Wanzhou, and a rise in interest for dog and cat meat amid China’s pork crisis, also featured in January.

China also announced that its economy grew by 6.1 per cent in 2019, marking the lowest growth rate since political turmoil ravaged the country in 1990.

In February 2020 the coronavirus, which at the time had killed more that 2,700 and infected over 78,000 in China alone, caused a backlog at Chinese ports due to travel curbs that kept workers away and so jammed up global supply chains. But China’s top container ports were able to loosen the backlog of cargo on their docks as workers returned towards the end of the month.

With face masks becoming a hotter topic, demand amid the coronavirus outbreak also created a severe shortage for China, the world’s largest producer of medical facial masks.

The coronavirus also caused cancellation of around two-thirds of the total number of flights scheduled every day in the month, placing huge financial pressure on airlines and airports, forcing China’s airlines to offer domestic flights for as little as US$4.

As of March 2020, the real impact of the coronavirus was known, and its impact on China’s economy was confirmed as combined data for

January and February showed that industrial production, retail sales and asset investment all declined far more than analysts expected.

By this stage, China was making more than 100 million face masks a day, up from 20 million before the coronavirus outbreak, and looked to export more to other countries. But mask shortages abroad again raised the debate about an over-reliance on China, with critics pointing to a lack of a US industrial policy.

A global shortage of coronavirus test kits sparked a scramble for resources, although the specialist nature of the production process posed quality concerns, with more than 100 Chinese companies selling kits to Europe even though most were not licensed to sell them in China.

Signs of China’s recovery from the coronavirus, though, began to emerge at the end of the month as China’s official manufacturing purchasing managers’ index (PMI) rose to 52 in March, rebounding from an all-time low in February and higher than forecasted.

In April 2020, a shortage of US dollars created by increased demand during the coronavirus threatened Chinese companies’ ability to raise new funds to pay off existing debts in April, but China was reluctant to project an image to the international community that it needed the US to provide it with easier access to the currency.

The impact of the coronavirus was also being felt by businesses in China, with confirmation that more than 460,000 firms had closed permanently in the first quarter.

China was also facing a fight to hang onto its foreign manufacturers as the US, Japan and the European Union made post-coronavirus plans, with calls to diversify supply chains finding growing support after the supply shock caused by China’s coronavirus shutdown.

China also claimed its stimulus was “10 times more efficient” than that of the US Federal Reserve, as Chinese banks pumped more than US$1 trillion into the economy in the first quarter of the year in an effort to stem the bleeding from the coronavirus.

China, though, confirmed its economy shrank by 6.8 per cent in the first quarter of 2020 after the coronavirus shut down large swathes of the country.

In May, US chip giant GlobalFoundries confirmed it had ceased operations at its sole Chinese facility, with industry experts saying the poorly planned project was doomed to fail.

US news reports suggested White House officials had already considered the idea of cancelling all or part of the US$1.1 trillion debt owed to China, with response to the debate over the highly unlikely “nuclear option” suggesting China could cut its holdings as the US ramped up borrowing to pay coronavirus-related costs.

A long-standing debate over whether China is a rich or poor nation was also reignited after the government released a series of divergent data sets on wealth in the world’s second-biggest economy.

A Deutsche Bank survey, meanwhile, indicated that 41 per cent of Americans would not buy “Made in China” products again, while 35 per cent of Chinese consumers would avoid US goods as the coronavirus fuelled mistrust among consumers on both sides of the Pacific.

In June 2020, the Hong Kong national security law began to the grab the headlines in June, with analysts saying the then-proposed legislation could mark the beginning of a process cutting China’s access to US dollars.

Risks of US financial sanctions also emerged for China after its National People’s Congress approved the national security law for Hong Kong, with Beijing left wondering whether Washington would cut it off from the US dollar payment system.

Another topic which would feature heavily for the rest of the year also emerged in June, with China’s Ministry of Commerce warning Australia that its new foreign investment policy should be “fair and non-discriminatory” to all countries, amid speculation that it was aimed at restricting investment from China.

China also unveiled plans to make Hainan a free-trade hub like Hong Kong and Singapore amid risks of economic decoupling from the US.

In July, it emerged that China bought more US debt in May despite talk of a financial war amid rising trans-Pacific tensions. Domestic debt also featured as Dushan county in the landlocked southwest province of Guizhou, one of the poorest regions in China, admitted to “reckless borrowing” after a video brought attention to a 40 billion yuan (US$5.7 billion) construction spree that began in 2016.

President Xi Jinping promised that China would stick to its “peaceful development” path, continue reform and deepen the opening of its domestic market in a letter to top international business executives.

Questions emerged over Australia’s share of China’s iron ore imports being at risk following the opening of four new ports along China’s coast that could operate berths for extra-large ships, opening up new possibilities for greater imports from Brazil and Africa.

China also avoided a recession after its economy grew by 3.2 per cent in the second quarter, the first major economy to show a recovery from the damage caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

As of August 2020, after earlier talk of firms leaving, China became increasingly worried about “losing face” as Japan offered a group of 87 companies subsidies totalling US$653 million to expand production at home and in Southeast Asia.

Construction on a US$20 billion state-of-the-art semiconductor manufacturing plant owned by Wuhan Hongxin Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (HSMC) in Wuhan also stalled due to a lack of funding.

China’s 290 million migrant workers were also facing the end of an era as the world’s factory wound down amid the coronavirus and the US-China trade war. One worker, Rao Dequn, who had worked for 25 years in Chinese factories making goods for overseas markets, was set to lose her job in less than a month.

Prominent Beijing adviser Yu Yongding, a senior fellow with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, warned that the US could not only sanction Chinese banks, but also seize overseas Chinese assets amid the bilateral financial row.

In September, analysts commented on how a critical mission for President Xi over the next 15 years was likely to be doubling the size of China’s “middle-income” group after Beijing reached its goal of eliminating absolute poverty by next summer.

Meanwhile, as the US ramped up its attacks on Chinese tech firms. As the threat of economic decoupling grew, government advisers in Beijing began debating the so-called nuclear option of cutting off US access to medicines.

Amid US pressure for ByteDance to sell or close down TikTok in the US, the Beijing-based company said it would not sell or transfer the algorithm behind the popular video-sharing app in any sale or divestment deal. And more than 800,000 Chinese students who had recently graduated from overseas universities returned home, more than ever before, adding to an already crowded domestic job market.

In October 2020 tensions between China and Australia began to dominate the headlines in October, with Canberra’s response to China’s ban on Australian coal exports hinting at a more conciliatory engagement with Beijing, although former diplomats and analysts said it was too early to tell if tensions had eased.

China’s informal verbal prohibitions on Australian imports of coal and cotton could, though, have breached rules set out by the World Trade Organization, as well as the free-trade deal between the two nations, according to trade lawyers.

A popular Japanese-themed shopping street in China’s Guangdong province was closed before the beginning of the “golden week” holiday, disappointing tourists and stoking speculation that copyright complaints and patriotism could have been behind the change.

Chinese families, meanwhile, were shunning Western universities as the coronavirus and strained ties were “scaring middle-class families”, with four out of five affluent Chinese parents with children studying foreign curriculums and taking foreign examinations saying they had postponed plans to send their children abroad.

China also confirmed that its economy grew by 4.9 per cent in third quarter as industrial production and retail sales grew by 6.9 per cent and 3.3 per cent, respectively, from a year earlier, while investment turned positive for the first time in 2020.

Tensions between China and Australia continued to dominate the headlines in November, with China banning imports of Australian timber from Queensland and suspending barley imports from a second grain exporter.

China’s commerce ministry also said that it would impose temporary anti-dumping measures on Australian wine imports.

A group of Chinese investors also withdrew their bid to purchase a A$80 million (US$58.5 million) office tower in Sydney after the Australian Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) delayed approval of the deal for eight months.

Elsewhere, analysts predicted that the administration of US president-elect Joe Biden would likely continue the Trump administration’s efforts to contain China technologically, despite the easing of some concerns about the acquisition of key American components needed for its home-grown C919 passenger jet.

In December, “star” bank manager Zhang Ying from Beijing was jailed for life for stealing the equivalent of US$400 million from clients and using the money to finance her lavish lifestyle.

Amid the ongoing tensions, Australian rock lobster all but disappeared from markets and restaurants in Beijing, since China imposed an import ban in November.

The China Iron & Steel Association (CISA) also said it had a “candid exchange of views” with Anglo-Australian miner BHP about soaring iron ore prices.

And a senior Chinese aviation engineer said it was an “urgent political task” for China to speed up development of its own jet engine as access to crucial technology was no longer guaranteed due to external hostilities, and that China must become more self-reliant.

Reported by the South China Morning Post.