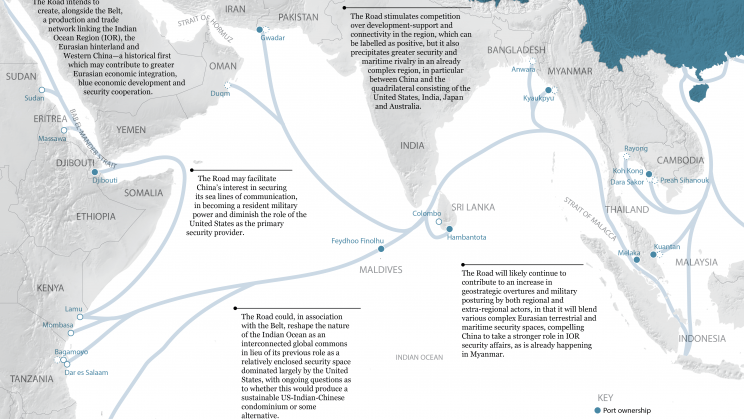

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a long-term Chinese vision for improved global connectivity, expanded production and trade chains, and closer overall cooperation.4 Thus far, the BRI has mainly focused on Eurasia and Africa. BRI recipient states.6 A number of these concerns apply to the Road. Moreover, the Road, and the BRI in general, was elevated by the Communist Party of China (CPC) to the constitutional level following the BRI’s fourth anniversary in October 2017.7 This reflects the strong political support from the CPC for sustaining the BRI as a red thread in Chinese foreign policy, and has significantly enhanced the Road’s strategic importance and longevity.8 Many observers both within and outside of China have come to associate the BRI with China’s President, Xi Jinping, and it has become a marker of his ambitious leadership. For years to come, a considerable allocation of Chinese political, financial, economic, diplomatic and human capital should be expected to be devoted to the initiative. This will be needed, as the Road is continually expanding its geographic scope. At its introduction in October 2013, the Road was oriented towards cooperation with the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN).9 The geographic scope, however, was not clearly defined. Sixteen months later, in the first official document on the Road, the initial ASEAN-centred focus had been supplemented by broader maritime coverage beyond the SCS and into the IOR, the South Pacific, the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic.10 In June 2017, China expanded the Road’s reach by incorporating the Arctic Ocean into the Road, often referred to as the ‘Polar Silk Road’.

Hence, the Road currently has three envisaged major arteries. The first and main artery goes from China’s coast to Europe through the SCS, the IOR and the Mediterranean Sea, and into the Atlantic. Its second artery extends from China’s coast through the SCS to the South Pacific and then onto greater Australia. The third artery extends through the Arctic Ocean, passing north-west alongside Russia’s northern coast to connect with the Nordic region and other parts of Europe, and north-east past Canada.11 Importantly, this expanding scope gives China and the states along the Road more strategic maritime space in which to act. China’s own maritime space lacks scope and depth. While China borders four seas—the Bohai Sea, the Yellow Sea, the East China Sea and the SCS—it is enclosed by the Korean Peninsula, Japan, the Philippines and Viet Nam. This is in stark contrast to US maritime space, which is largely open and exclusive on both the Atlantic and the Pacific side, and the European Union (EU), which is only enclosed along its southern fringes by North Africa. In contrast to the Atlantic and the Pacific, or the most strategic spaces of Central and South Asia traversed by the Belt, the SCS and Indian Ocean are more complicated and contested security spaces to which China’s maritime renaissance adds.

Alongside its expansion in geographic scope, the Road has also undergone a strategic evolution. As an adaptable and evolving initiative, the Road seeks to embrace any strategic opportunity that enhances China’s national strength and serves its core interests.12 In particular, this involves sustaining China’s continuing economic growth The Road, which is the maritime/coastal component of the BRI, focuses on creating a network of ports, through construction, expansion or operation, and the development of portside industrial parks and special economic zones (SEZs). In this way, the Road, in tandem with its terrestrial complement, the Silk Road Economic Belt (the ‘Belt’), fills a connectivity gap in large economically heterogeneous parts of Asia and Africa and has no peers that approximate its scale and speed. Alongside the enthusiasm and spirit of cooperation on economic development and connectivity among some 90 countries and international organizations, including the United Nations, the BRI has caused strategic and security concerns among a number of stakeholders. Among these, the most outspoken are Australia, India, Japan, Viet Nam and the United States; France, Germany and the United Kingdom in Europe; and critical political elites and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in some by furthering development of the blue economy, which contributed to 9.4 per cent of China’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2017, or more than $1.2 trillion.13 In China, the concept of the blue economy is broadly regarded as ocean-related industry and the utilization of ocean-related resources.

This approach differs from that increasingly found among Western countries and NGOs, where environmental sustainability, or ‘greening’, has gained more weight in decision-making processes.15 Hence, the environmental implications of a number of Chinese Road investments in host countries and adjacent waters have fuelled criticism among local and Western stakeholders.16 Moreover, China’s inability to curb domestic air, soil and water pollution has raised doubts about whether its foreign Road investments will be green. Against this backdrop, China has been proactively pursuing marine sustainability by promoting green investment and development, and through international frameworks such as the 2016 Paris Climate Agreement. In addition, the Road intends to synchronize its efforts with the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This shift in approach is also evident in China’s BRI White Paper of June 2017, Vision for Maritime Cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative.

The paper addresses ‘green development’ by providing concrete policy guidance, setting up monitoring systems and proposing cooperation on environmental improvement.18 By contrast, the first BRI White Paper, published in 2015, Vision and Actions on Jointly Building the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, only briefly referred to the importance of environmental safeguards.19 The 2017 White Paper recognizes mutual ‘maritime security’ as protection from traditional and non-traditional security threats to good order at sea, and that the Road serves as a key assurance for developing the blue economy. Maritime security was not mentioned in the 2015 document. These documents illustrate how China is learning and adapting as the Road project evolves. According to one prominent Chinese BRI-shaper, the initiative is ‘barely a five-year old kid that is still making mistakes and still learning’.

China is now seeking to incentivize maritime cooperation in domains of common security interest such as maritime navigation security, search and rescue missions and marine disaster response, as well as maritime law enforcement.21 Alongside maritime security and ‘green’ development, China has prioritized ‘collaborative governance’, ‘innovative growth’ and ‘ocean-based prosperity’. This inter-state cooperation and synchronization of the maritime development plans of the states along the Road could encourage the collective tackling of non-traditional security challenges. However, it is too early to take a firm stance on this. What is evident is that the Road permits China to lead and promote maritime cooperation and governance along its routes and coshape the future maritime order.

What is China seeking to achieve by establishing the Road? To understand this, it is necessary to briefly delve into China’s maritime history. While China has long been considered a continental power, it also had a rich maritime history, some of which was part of the old Silk Roads. China’s maritime capabilities arguably peaked during the Ming Dynasty in the first half of the 15th century. Through a history of lost sea battles in the past 200 years and by observing the rise and decline of more contemporary powers, China has learned that a global power must possess strong maritime power: ‘weak maritime power leads to a declining nation; strong maritime power leads to a strong nation’.

The importance of achieving a ‘maritime renaissance’ has been addressed ever since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, but progress has lagged behind its achievements in other military and nonmilitary domains.23 Backed by a clear vision and political backing, China’s maritime power is catching up now that it has overcome its dwindling economy and relative technological backwardness of the 20th century.24 Indeed, the Chinese leadership has increasingly turned its attention to maritime interests. At the 18th National Congress of the CPC in November 2012, then President of the China, Hu Jintao, declared China’s ambition to become a strong maritime power.25 This ambition was repeated in China’s Defence White Paper in 2013 and again in 2015.26 The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has since shifted its focus from offshore waters defence to open seas protection, or becoming a blue water navy that is capable of protracted operations in the open oceans and that has the ability to project power even in distant waters.27 This shift is crucial for China because expanded investment through the Road requires a stronger PLAN to protect its overseas interests, citizens and assets. Unlike the USA, China still lacks an adequate naval network and capacity.28 It is also driven, however, by unresolved maritime and jurisdictional disputes in the East China Sea and the SCS. In addition to these disputes, the US ‘Rebalance to Asia’, which commenced in 2011 to demonstrate that the USA had the will and resources to remain fully engaged in East Asia, helped to accelerate China’s increase in maritime power to secure its maritime interests. The Road is a key instrument in achieving these objectives, if only by securing strategic ‘real estate’ and related geostrategic and security benefits.29 Chinese investments in unstable regions and fragile states also carry significant risks to the Chinese economy. Given China’s economic weight in the global economy, if these substantial investments were to turn sour, the increasing economic and political cost could lead to strategic overreach and indirectly even impact the global economy.

China’s maritime interests should not be understated as they are grounded in China’s core interests—or non-negotiable—interests. China’s core interests are: (a) its political system and state security; (b) state sovereignty and territorial integrity; and (c) the continued stable development of the economy and society.These three interests have since been expanded to seven: (a) the regime; (b) sovereignty; (c) unity; (d) territorial integrity; (e) the welfare of the people; (f) sustainable economic and social development; and (g) other major interests of the state and the capability to maintain a sustained security status.

State sovereignty, territorial integrity, regime stability and sustainable economic and social development are the four key components of China’s core interests. These are also the basic guidelines for China’s maritime interests and the benchmarks for the key security interests that China intends to establish through the Road. Despite these guidelines, like the Belt, the Road did not have a single event or driver that led to its genesis. Rather, it is an aggregation of a number of drivers. In Chinese and international discourse on the BRI there is much talk of the Road, or more accurately the BRI, serving as a Chinese style of globalization. This suggests that the initiative has grandiose objectives for a Chinese-led style of global development that will lead to a China-centric economic order. While this notion certainly has some substance, as is largely covered in the SIPRI–FES report on the Belt, the drivers are still rather opaque and may not have been that well developed at the outset by Chinese strategic thinkers at the highest levels.

This analysis therefore prefers to focus on the more obvious interests outlined below. It should be noted that since the Road is a long-term initiative, as Chinese and global dynamics change, so may China’s aspirations for the Road. The ocean, the largest and most critical ecosystem on Earth, is becoming a new focal point in the global discourse on growth and sustainable development. In many ways the world is at a turning point in setting its economic priorities for the ocean. China does not want to be left out.

In 2012–17, China’s blue economy grew by an average of 7.5 per cent annually. It currently accounts for nearly 10 per cent of China’s GDP, and the aim is to expand this to 15 per cent of GDP by 2035. With nearly 90 per cent of China’s total international trade by volume and some 60 per cent of trade by value transported by sea, maritime trade is the primary engine sustaining China’s national economy.36 Through the Road’s ‘Blue Partnerships’, China can export its industrial overcapacity to overseas markets and foster new sources of growth for its domestic and the local economy, some of which are tied to emerging growth niches in the blue economy. To this end, and among other drivers, China has actively started to seek ownership of foreign seaports along strategic transit channels through land-use agreements between Chinese state-owned enterprises and local authorities, many of which are in the IOR.

Investment in these ports, port-affiliated infrastructure and SEZs throughout the Road is intended to stimulate the local blue economy, connect with China’s coastal areas and in a number of cases—such as Gwadar in Pakistan and Kyaukpyu in Myanmar, so-called gateway ports—stimulate the redevelopment of China’s terrestrial economy by connecting China’s less-developed inland provinces through the economic corridors along the Belt to the Indian Ocean.

It is evident that China is seeking to merge terrestrial and maritime infrastructure along the Belt and the Road into a mega production and trade network that can create synergies between the traditional and the blue economy. However, it should be noted that while the Belt is creating valuable land ‘lifelines’ for energy and goods across Eurasia to China, these, with a few exceptions, cannot compete with the volume-price ratio of seaborne trade. For this reason, China is seriously pursuing the development of both its terrestrial and its blue economy and the Road should not be seen as a standalone project. The Belt and the Road are very much a mutually synergizing whole.

All economies, particularly rising powers, seek to mitigate risks to their supply chains and China is no exception. The potential for economic or diplomatic isolation, such as that imposed by the USA on China in the 1950s and again in the 1990s, has been taken seriously by the Chinese Government. China has become highly committed in its drive to strengthen its resilience, or more accurately its ‘geo-economic resilience’, to threats that could affect its socio-economic stability and consequently regime security.40

The recent trade and tariff disputes with US President Donald J. Trump’s Administration reinforces this rationale. The need to improve resilience also applies to China’s food security. With a population of about 1.4 billion, food security is key to domestic stability. There is a growing demand from China for food imported by both land and sea. As a share of total merchandise imports, Chinese food imports increased from 3.2 per cent in 2006 to 6.3 per cent in 2016. In 2017, 43 per cent of Chinese staple food imports passed through the Malacca Strait and 39 per cent through the Panama Canal. Both of these are choke points, or narrow channels along widely used global sea lanes, under the protection and surveillance of the US Navy. China only has a limited maritime capacity and presence in these waters. These imports are thus subject to a risk of US Navy interdiction. In tandem, China has also addressed the importance of establishing overseas bases for food production, processing and storage. As a result, in the past decade Chinese companies have engaged in a variety of land-, food- and agriculturerelated acquisitions in South East Asia, Russia, Australia, Latin America and the USA.42 For example, China is now the second largest foreign agricultural landholder in Australia, with 9 112 000 ha, just 0.1 per cent behind the UK. Such acquisitions indirectly help to secure China’s domestic food supply by increasing global food production.

Seeking rights of utilization over land and resources in foreign countries is a recurring pattern and part of China’s long-term calculus for mitigating geopolitical and economic risks.45 To transport these agricultural supplies to China, improved and diversified terrestrial connectivity through the Belt and maritime connectivity through the Road are essential. Improving resilience also applies to China’s energy security. In 2017, China surpassed the USA as the world’s largest importer of crude oil. By 2035, China will need to import approximately 80 per cent of its oil to meet demand, compared to 64 per cent in 2016.46 China is heavily dependent on oil imports from the Middle East and Africa. Its transit routes all pass through the IOR and the SCS, and 80 per cent of these seaborne imports pass through the Malacca Strait.47 As a result, China is deeply concerned about its dependence on the South East Asian straits, of which the Malacca Strait is the most often highlighted among all of the straits around the Malay Peninsula. Hu Jintao spoke of this concern in 2003 following an increase in the US naval presence around the South East Asian straits. Chinese media and scholars dubbed the address the ‘Malacca dilemma’, stressing the challenges to China’s international trade and energy security.48 Much of this is linked to the fear that the US Navy could interdict the transit of energy supplies and hence affect China’s energy security.

That said, the viability and sustainability of a blockade strategy is debatable. With the exception of the Suez crisis in 1956, state fragility and armed conflicts have barely ever resulted in blocked choke points. Moreover, the costs of a restriction on China’s access to the South East Asian straits would not only affect China’s economy, but also harm the economic interests of the USA and its allies. In fact, one senior analyst has pointed out that since the end of World War II, there have barely been interdictions of commercial transit in the IOR or the SCS because such transit tends to be multi stakeholder. It is, however, in the CPC mindset to prepare for the worst and to alleviate sources of vulnerability, rather than hope for the best. Evidence of this can be found in China’s efforts to develop the China–Myanmar natural gas and oil pipelines that run from Kyaukpyu port to Kunming. The pipeline’s goal is to reduce China’s heavy reliance on the South East Asian straits.

Reducing dependence on the US Navy by securing existing routes through the PLAN and the creation of alternatives through the Road and the Belt are crucial to China. This is important not only because of the above-mentioned potential for interdiction at choke points, but also at the structural and long-term levels. Therefore, another key objective of the Road is to pave the way for China to secure its sea lines of communication (SLOCs), the primary maritime routes between ports used for trade, logistics and naval forces. In China’s case this translates into an assurance of strategic or unimpeded access to vital international sea routes. The importance of access to a diverse and secure range of SLOCs cannot be overstated as this defines the territorial reach and physical capabilities of China and is integral to the achievement of its political, economic and military potential.

Therefore, it should be expected that as the Road’s footprint grows, the PLAN is very likely to follow suit. This dynamic is symbiotic: the PLAN needs reliable logistical chains to resupply food, fuel and armaments across the SLOCs, which in turn can be used to secure the SLOCs. In terms of the role of the Road, this requires the building of logistical infrastructure at strategic locations in key states. For example, Gwadar port—which is 400 km from another potential choke point, the Strait of Hormuz— could play an important role in helping the PLAN monitor the SLOCs in the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf, or at least gain access to critical port facilities.

It should be noted however that the port is currently solely for commercial use. In turn, the lease by China of the port and military base in Obock, Djibouti, will enable the PLAN to project power around the Horn of Africa. This base demonstrates China’s ambition to be a maritime power not just in the Pacific, but also in the Indian Ocean.54 Securing SLOCs that run through both the Pacific and the Indian Ocean will require China to project maritime power in both oceans. Projection in only one of them would make little sense.

The Road can be seen as a soft power attempt by China to resolve maritime and jurisdictional disputes in the SCS with four South East Asian claimants. China’s maritime claims in the SCS, and the East China Sea for that matter, have become core interests. China sees the East China Sea and the SCS as strategically allied against it through an S-shaped US-led alliance from South Korea to Japan to Taiwan (China) to the Philippines and on to Australia. China is trying to fracture this alliance and the SCS plays a key role in this. The SCS had been mostly tranquil since the 1980s, but disputes were reignited in 2009 when China claimed sovereignty over disputed waters using its nine-dash line, which makes a claim to close to 80 per cent of SCS waters.

The US response, ‘Freedom of Navigation’, published in 2010, further exacerbated tensions and these have continued to linger. The SCS disputes are at an impasse and unfavourable political and social undertones prevail in the region. While China’s 2017 BRI White Paper mentions upholding the existing international maritime order, China’s rejection of a ruling by the International Court of Arbitration in The Hague in 2016 risks international acceptance of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which China ratified in 1996 in spite of the fact that the USA has not ratified it. The rejection showed a side of China that does not necessarily abide by a rules-based order when its core interests are at stake.

China is attempting to build trust and improve bilateral ties with countries through the Road. From a Chinese perspective, common economic interests can improve political and security cooperation among countries. Hence, Chinese academics have argued that SCS disputes should not affect economic cooperation and long-term relations between the claimants, even if China’s maritime claims in the SCS are classified as a core interest.

Thus, with the Road, China has reprioritized economic development over territorial disputes—for now. However, this does not mean that China is willing to compromise on its nine-dash line claims. In fact, through the Road, China could bolster its economic and political leverage, and maritime power projection in the SCS. In the medium to long-term, this could undermine naval navigation freedom and economic influence of the USA and its allies, and enable China to resolve disputes with claimants bilaterally at ‘favourable’ moments.

As part of its maritime aspirations, China intends to shape the future international and regional maritime order in the SCS, the IOR and beyond into one that favours Chinese interests.56 To achieve this goal, China is seeking to increase its international discourse power through the Road. Discourse power is an important soft power that not only affects prevailing political values, regional norms and narratives, but can also introduce new values, as they relate for instance to diplomacy, and shape agendas, as they relate for example to syncing development priorities.

With its growing economic power, China is no longer willing to remain behind in the shaping of the international discourse. Its leadership has realized that although the USA remains the world’s largest economy, China is now the world’s most effective economic shaper. As such, China is seeking to challenge and corrode ‘Westerncentrism’ and balance it with a China-led economic order. One example is the ‘China solution’ to global governance. This solution aims to provide the Global South with alternatives based on the Chinese development model, which differs from the US-led consensus.58 Maritime access plays a significant role in this context as it eases the formation of shared security interests, strategic alliances and improved security ties.

This does not mean that China is completely at odds with military cooperation with the West. In fact, the PLAN plays an active role in anti-piracy operations together with the EU and welcomes cooperation with the USA. Such cooperation on non-traditional security issues bolsters China’s favourable maritime image among Road-participating states. To better understand this dynamic, chapter 2 sheds light on perceptions of the Road in the SCS and the IOR, and examines its security implications for these regions.

Taken from Richard Ghazy, Fei Su and Laura Saalman: The 21th Century Maritime Silk Road, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.